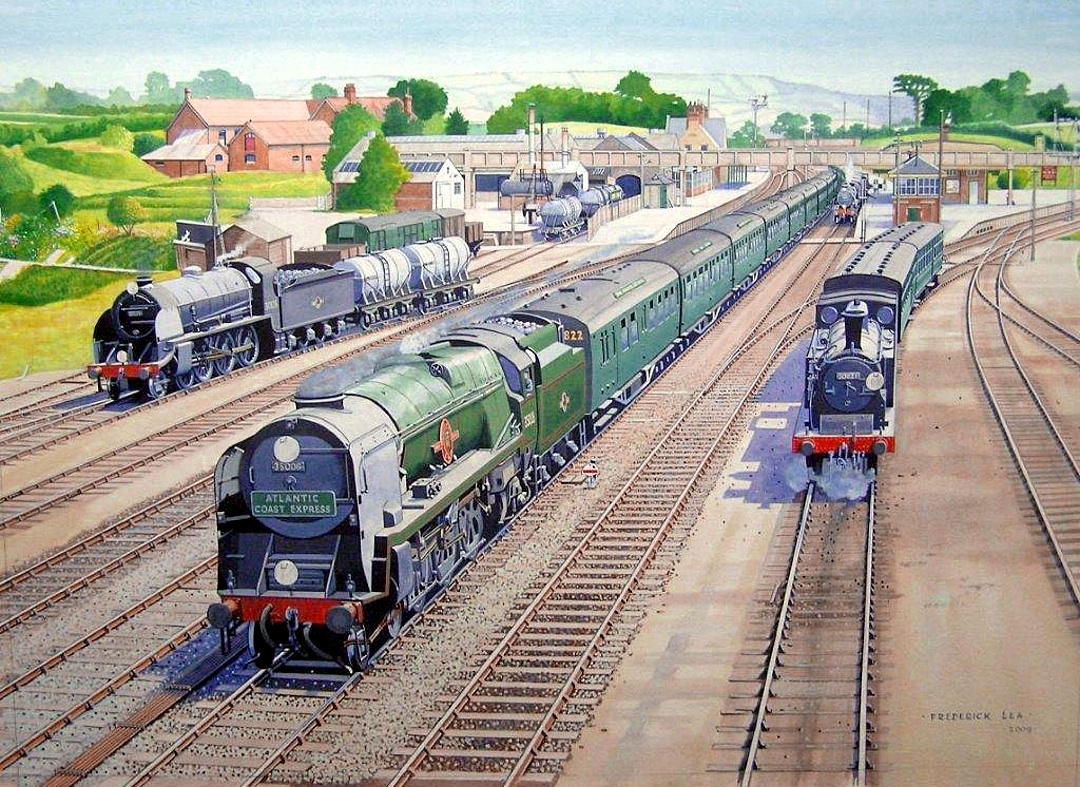

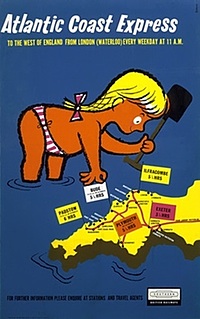

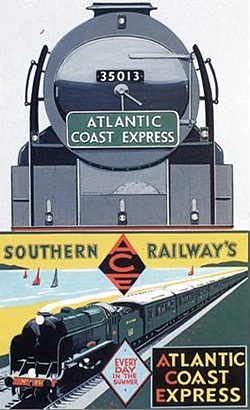

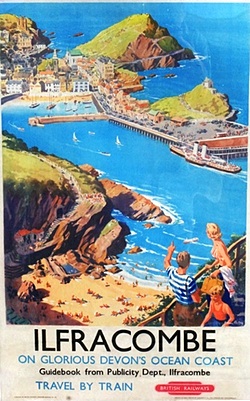

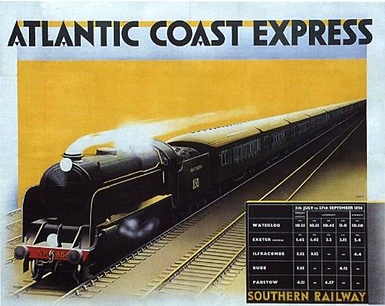

In the 90 odd years since Southern Railway’s Atlantic Coast Express (known simply as the ACE) first debuted at Waterloo station at 11.00am on 19 July 1926, the West Country express became one of the nation’s most instantly recognised named trains. It’s a bygone era where magical memories of relaxed holidays in the countryside and by the sea are instantly recounted. And an express service it most certainly was utilising Southern’s most powerful locomotives running over the fast legs from London, Salisbury and into Devon and then only slowing up as it served the many stations north and west of Exeter. The inaugural run served just five destinations; stations in Devon – Plymouth, Torrington and Ilfracombe and the Cornish resorts of Bude and Padstow – the most westerly of Southern Railway’s destinations and some 260 miles from its Waterloo headquarters: Sidmouth and Exmouth stations were added in 1927. By the time the service was suspended for the war years on 10 September 1939 the ACE in every sense of the word had established itself as an iconic named train rivalling the Great Western Railway’s (GWR) long-established Cornish Riviera Express. Notwithstanding, the two companies fought over the bragging rights of who provided the best West Country service for many years but in truth some degree of marketing collaboration took place between them both and with the various tourism boards of Devon and Cornwall.

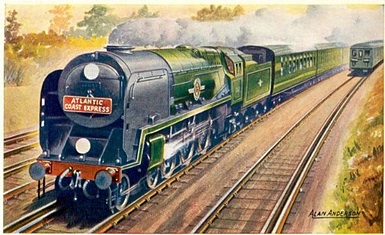

The ACE’s reputation was not to be disrupted by the war years. Following resumption of the service on 6 October 1947 the routes to the Withered Arm had new and powerful motive power with Merchant Navy, West Country and Battle of Britain locomotives together with new Bulleid and Mk1 coaching stock. The new locomotives had a look, style and art-deco streamlined design that certainly caught the imagination of the travelling public. Across the West Country the modern Pacific locomotives could be seen in almost every nook and cranny of the former LSWR metals. Modernity and heritage were strange bedfellows but Southern Railway and later British Railways Southern Region BR(S) over the next 15 years constantly sought to capitalise on these assets by developing themes and images for the ACE’s promotional output often reflecting a subtle form of superiority over the destinations served by the Cornish Riviera Express. During this period however, the service was further enhanced with significant acceleration of the Waterloo originated West Country train.

The ACE’s reputation was not to be disrupted by the war years. Following resumption of the service on 6 October 1947 the routes to the Withered Arm had new and powerful motive power with Merchant Navy, West Country and Battle of Britain locomotives together with new Bulleid and Mk1 coaching stock. The new locomotives had a look, style and art-deco streamlined design that certainly caught the imagination of the travelling public. Across the West Country the modern Pacific locomotives could be seen in almost every nook and cranny of the former LSWR metals. Modernity and heritage were strange bedfellows but Southern Railway and later British Railways Southern Region BR(S) over the next 15 years constantly sought to capitalise on these assets by developing themes and images for the ACE’s promotional output often reflecting a subtle form of superiority over the destinations served by the Cornish Riviera Express. During this period however, the service was further enhanced with significant acceleration of the Waterloo originated West Country train.

From September 1962 British Railways Western Region – BR(W) began to take responsibility for the line west of Salisbury with full control of the Withered Arm routes passing on 1 January 1963. The famous holiday express at its conclusion was headed by Western Region Warship diesel-hydraulic locomotives commencing and finishing journeys to and from Waterloo. Railway pundits suggest BR(W) did their best to exact revenge by ensuring the old London & South Western Railway (LSWR) route to the West Country was relegated to secondary line status. If this was not bad enough for Southern stalwarts the route eventually suffered the ignominy of single track reduction for large parts of the Salisbury – Sherborne – Exeter section. The axe had been swung with a vengeance on the Withered Arm’s rural community routes. As Devon and Cornwall morphed into mass tourism destinations served by the car, the ACE as a famous named train was consigned to history on 5 September 1964.

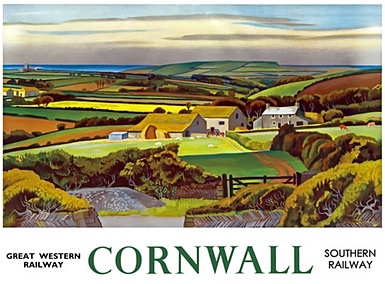

The origins of the ACE can be traced back to late Victorian times when the LSWR eyed up and probed GWR’s territory in order to develop new routes beyond Exeter: This was home turf competitive encroachment as the GWR considered Devon and Cornwall to be its own back yard. They had maintained a stranglehold of the best routes to the counties of the far south west. Although the LSWR had absorbed the Bodmin and Wadebridge line long ago in 1846 the two railways (GWR and LSWR) battled it out over Cornwall but LSWR’s eventual penetration of North Cornwall with various connections did not come about until the end of Victorian age; Bude was reached in 1898 and Padstow a year later in 1899. GWR had previously surveyed the rugged landscapes of North Cornwall with its string of small resorts but disregarded its tourist and passenger potential – a decision it was to regret at the height of the ACE’s popularity.

The origins of the ACE can be traced back to late Victorian times when the LSWR eyed up and probed GWR’s territory in order to develop new routes beyond Exeter: This was home turf competitive encroachment as the GWR considered Devon and Cornwall to be its own back yard. They had maintained a stranglehold of the best routes to the counties of the far south west. Although the LSWR had absorbed the Bodmin and Wadebridge line long ago in 1846 the two railways (GWR and LSWR) battled it out over Cornwall but LSWR’s eventual penetration of North Cornwall with various connections did not come about until the end of Victorian age; Bude was reached in 1898 and Padstow a year later in 1899. GWR had previously surveyed the rugged landscapes of North Cornwall with its string of small resorts but disregarded its tourist and passenger potential – a decision it was to regret at the height of the ACE’s popularity.

Over the years there had been many tussles between the GWR and LSWR and, perhaps, none was more graphic than the headlong engagement the two companies had with each other as they tried to develop the spoils of blossoming North Atlantic liner port of call passenger traffic departing and landing at Plymouth. By the early years of the 1900s the GWR had effectively seen off LSWR maintaining lucrative bullion and mail contracts and conveying prosperous passengers wishing to disembark liners at the earliest possible opportunity. Up until then the GWR and the LSWR had fought hard to maintain their respective liner traffic shares over the different routes to Plymouth. However, the competitive nature of this spat was to end in 1906 when a LSWR ocean special crashed at speed in Salisbury. Plymouth liner traffic was left to GWR but LSWR refocused its attentions to developing Southampton as an alternative port which it had owned since 1892. Whilst the LSWR had maintained a regular 11.00am departure from Waterloo for the West of England since the early 1890s, there was never a degree of panache associated with the service; the company never naming any of their timetabled trains or indeed even their locomotives. The full potential of the Exeter, North Devon, Plymouth and North Cornwall routes for travelling passengers (and also significant agricultural and fisheries freight traffic) was never really recognised until after grouping a quarter of a century later.

Over the years there had been many tussles between the GWR and LSWR and, perhaps, none was more graphic than the headlong engagement the two companies had with each other as they tried to develop the spoils of blossoming North Atlantic liner port of call passenger traffic departing and landing at Plymouth. By the early years of the 1900s the GWR had effectively seen off LSWR maintaining lucrative bullion and mail contracts and conveying prosperous passengers wishing to disembark liners at the earliest possible opportunity. Up until then the GWR and the LSWR had fought hard to maintain their respective liner traffic shares over the different routes to Plymouth. However, the competitive nature of this spat was to end in 1906 when a LSWR ocean special crashed at speed in Salisbury. Plymouth liner traffic was left to GWR but LSWR refocused its attentions to developing Southampton as an alternative port which it had owned since 1892. Whilst the LSWR had maintained a regular 11.00am departure from Waterloo for the West of England since the early 1890s, there was never a degree of panache associated with the service; the company never naming any of their timetabled trains or indeed even their locomotives. The full potential of the Exeter, North Devon, Plymouth and North Cornwall routes for travelling passengers (and also significant agricultural and fisheries freight traffic) was never really recognised until after grouping a quarter of a century later.

In 1926 the newly created Southern Railway set about establishing the ACE with a degree of zeal, enterprise and a new public relations broom. This followed the company’s appointment of its first public relations guru J.B. (later Sir John) Elliot. The ACE name was adopted following a staff suggestion scheme run in the July issue of the Southern Railway Magazine. When the ACE service was launched Southern had a certain degree of catch-up to play as Devon and Cornwall had been consistently promoted by GWR’s fleet-footed Paddington publicity department for the best part of the previous 25 years. Part of GWR’s strategy was to deliberately position itself alongside the region’s premier destinations where it was seen very much as a co-operative partner in developing the visitor economy. Elliot, therefore, had to counter well-oiled GWR machinery which required the Southern Railway to create a complete new identity for the train. More importantly, the ACE destination image needed to be fresh, in sympathy with the region’s natural assets, Cornish Celtic heritage and as Tennyson wrote the need to portray North Cornwall as ‘King Arthur Country’. The business imperative was to prise customers from GWR’s Cornish Riviera service and to drive thousands of new middle class fare paying passengers to Southern’s upmarket routes and destinations. The new image could be wrapped up by the word ‘Adventure’ – a frisson of excitement and anticipation associated with visiting King Arthur’s Kingdom.

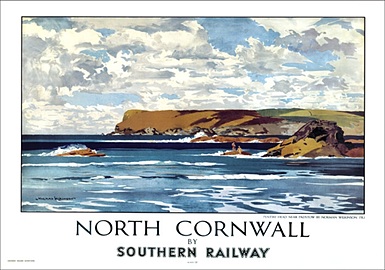

Elliot also sought to capitalise on Arthurian legend by developing this part of the West Country as a special place aided by the works and contributions of the future Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman who was well-known for his support of architecture, heritage, landscape and the railway system. Betjeman and his friend Jack Beddington the publicity manager for Shell-Mex Ltd were responsible for developing the ‘Shell Guides’ – a series of highly successful county based motoring guides catering for Britain’s growing numbers of car drivers. The Cornwall edition was written by Betjeman in 1934 and Devon in 1936. Elliot’s thinking was to align Southern Railway’s connections with evolving public fascination in the West Country. In time North Cornwall simply became known as ‘Betjemanland’ as he continued to make regular journeys along the Withered Arm to the Cornish paradise of Padstow. The spirit of North Cornwall and its moods was also captured by Elliot as he commissioned railway poster work created by marine artist Norman Wilkinson who held a life-long fascination with the sea. The sum of the whole brought about a new dimension to Southern Railway’s travel marketing.

Elliot also sought to capitalise on Arthurian legend by developing this part of the West Country as a special place aided by the works and contributions of the future Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman who was well-known for his support of architecture, heritage, landscape and the railway system. Betjeman and his friend Jack Beddington the publicity manager for Shell-Mex Ltd were responsible for developing the ‘Shell Guides’ – a series of highly successful county based motoring guides catering for Britain’s growing numbers of car drivers. The Cornwall edition was written by Betjeman in 1934 and Devon in 1936. Elliot’s thinking was to align Southern Railway’s connections with evolving public fascination in the West Country. In time North Cornwall simply became known as ‘Betjemanland’ as he continued to make regular journeys along the Withered Arm to the Cornish paradise of Padstow. The spirit of North Cornwall and its moods was also captured by Elliot as he commissioned railway poster work created by marine artist Norman Wilkinson who held a life-long fascination with the sea. The sum of the whole brought about a new dimension to Southern Railway’s travel marketing.

With Betjeman’s developing career as a writer and broadcaster Elliot tapped into this rich vein of interest in rural affairs by developing a promotional strategy that involved another prolific British author, journalist and broadcaster S. P. B. Mais. He was commissioned by Elliot’s department to write about the various routes of the ACE. Mais was an ardent campaigner for the English countryside and its traditions becoming what would be described today as a ‘celebrated travel writer’ whose considerable and prolific output also included work for the company’s arch competitor the GWR. His writings were packaged by Elliot in a Southern Railway booklet produced in 1936 entitled ‘Let’s Get Out Of Here’ – a guide to walks from the route of the ACE. This was quickly followed by a second booklet published in 1937 and known simply as ‘ACE’. This well-known book portrayed a whimsical look of the train’s journey supported by many evocative drawings and illustrations by muralist and artist Anna Zinkeisen informing passengers of what could observed from each coach compartment. Southern Railway had recently introduced new Maunsell designed coaching stock that replicated successful ideas introduced by other railway companies – one of the key passenger focused features used in the new carriages was the inclusion of wide window bays. In addition, for the railway S.P.B. Mais’s text importantly explored the beauty and seasonality of the route as the ACE became a year round service. These developments saw a significant surge in passenger traffic in the late 1930s particularly as the ACE’s eastern upscale resorts of Budleigh Salterton, Sidmouth and Lyme Regis became more popular. Coupled with the Bournemouth and Weymouth line, the ACE service firmly cemented the south west division of the Southern Railway as one of the country’s busiest series of railway routes.

Waterloo station would pullulate with travelling passengers especially on summer Saturdays. The ACE adventure would depart from the middle of the station concourse from platforms 10 and 11. The train was designed as a multi-portioned express with eight sections and separate coaches for the more easterly stations of Sidmouth, Exmouth and Exeter, the north Cornwall destinations Bude and Padstow, Plymouth and finally the north Devon section for Torrington and Ilfracombe. During the summer months when traveller demand was high two trains would run daily apart from Saturdays when the train would run in four parts. At times however, there may have been as many as six separate trains to cope with the numbers of passengers heading west (calculated at some 3,800 bookings for seats) for ACE’s various destinations. Whether the ACE could be described as a truly luxury train has been questioned as its unique composition gave the impression of being like a parcels train. What is without debate is the train’s celebrity status being very well-appointed for both first and third-class travellers and quickly establishing itself as one of Southern Railway’s two flagship services but one to never carry a Pullman specification unlike the Golden Arrow.

Waterloo station would pullulate with travelling passengers especially on summer Saturdays. The ACE adventure would depart from the middle of the station concourse from platforms 10 and 11. The train was designed as a multi-portioned express with eight sections and separate coaches for the more easterly stations of Sidmouth, Exmouth and Exeter, the north Cornwall destinations Bude and Padstow, Plymouth and finally the north Devon section for Torrington and Ilfracombe. During the summer months when traveller demand was high two trains would run daily apart from Saturdays when the train would run in four parts. At times however, there may have been as many as six separate trains to cope with the numbers of passengers heading west (calculated at some 3,800 bookings for seats) for ACE’s various destinations. Whether the ACE could be described as a truly luxury train has been questioned as its unique composition gave the impression of being like a parcels train. What is without debate is the train’s celebrity status being very well-appointed for both first and third-class travellers and quickly establishing itself as one of Southern Railway’s two flagship services but one to never carry a Pullman specification unlike the Golden Arrow.

To understand this position it’s necessary to look at the history of Pullman services to the south west of England. There had always been a complete dearth of Pullman services to the West Country: GWR had had its Cornish Riviera Express since the early years of the 20th century which was a pretty luxurious affair that was widely promoted almost as an unique brand. The company dabbled with Pullman services for two summer seasons before launching its own ultra-luxury equivalent with the Super Saloons in 1931. The short-lived and largely unsuccessful Devon Belle Pullman service over Southern metals did not appear until after WW2 so over the years there was effectively a complete absence of Pullman to the far south west. Moreover, before grouping the LSWR as a former Southern Railway constituent company did not have a track record of courting the Pullman Company in the same ways as near neighbours LBSCR and SECR had done. LSWR had experimented with Pullman provision for a couple of years but eschewed a longer-term relationship preferring to develop its own catering and sleeping car services. LSWR developed new specialist stock for Plymouth Ocean Liner traffic but this was later sold following the company’s withdrawal from direct competition with GWR – ironically the sleeping carriages sold to the same company.

So no Pullman for the ACE: When it launched it had to make-do with a mixture of existing pre-grouping LSWR coaches (including Ironclad carriages) and post 1923 Southern stock for a short while. The ACE was a very heavily loaded train with its initial formation of largely single coach sections of composite first, third and brake. David St John Thomas and Patrick Whitehouse in their history of the Southern Railway suggested the train at its outset was no marvel. They didn’t mince their words commenting “Riding (on the ACE) was rougher than on the Great Western, seating infinitely inferior to the LMS, picture windows slow to appear and woodwork rougher hewn”. However, this second-rate product was not to last as new Olive liveried Maunsell steel-panelled bogie restaurant cars consisting of a first-class kitchen car and a third-class open salon were introduced to the ACE in 1928.

So no Pullman for the ACE: When it launched it had to make-do with a mixture of existing pre-grouping LSWR coaches (including Ironclad carriages) and post 1923 Southern stock for a short while. The ACE was a very heavily loaded train with its initial formation of largely single coach sections of composite first, third and brake. David St John Thomas and Patrick Whitehouse in their history of the Southern Railway suggested the train at its outset was no marvel. They didn’t mince their words commenting “Riding (on the ACE) was rougher than on the Great Western, seating infinitely inferior to the LMS, picture windows slow to appear and woodwork rougher hewn”. However, this second-rate product was not to last as new Olive liveried Maunsell steel-panelled bogie restaurant cars consisting of a first-class kitchen car and a third-class open salon were introduced to the ACE in 1928.

There was no other named train quite like it characterised by its almost unique collection of brake composites (as many as eight out of ten vehicles) for the many different end destinations the ACE would serve: Indeed, it was recognised as the country’s most multi-portioned train service. Their inclusion added a distinct flavouring as the formation could change according to time of year and week. New stock provided travellers with an exceptional level of spacious and comfortable first-class accommodation. Large 36 ton dining cars would travel as far as Exeter or when the North Devon portion ran as a separate relief train to Ilfracombe. Whilst the multi-portioned ACE did restrict some movement around the train (similar to the GWR’s Cornish Riviera Express with its slip coach sections), it was nonetheless a fast and efficient luxury train service for first-class passengers, who courtesy of the train’s brake composite carriage make-up, never had to worry about their holiday luggage or to think about changing coach or train to reach their desired West Country destination. The different sections of the ACE also created an unique cosmopolitan flavour coupled with a degree of camaraderie as fellow passengers were urged to converse with each other about their holiday plans and the places they would visit. The train was very much in vogue in the 1930s coupled to Elliot’s promotional output. Word of mouth discussions were recognised as powerful tourism ploys. In modern marketing parlance the ACE was a ‘tailored’ customer service. For passengers it was a premier named train that actually served the many smaller stations of east Devon and the destinations of the Atlantic shores of North Cornwall and Devon.

By late 1938 some of ACE’s south west section locomotive hauled Maunsell sets were repainted in the new light green or Malachite green livery. In September 1939 the ACE’s title immediately disappeared from timetables and a slower service with additional stops ensued. After the war years new Bulleid coach stock started to appear from early 1946 which transformed the ACE. These coaches were considered not to be radically different to Maunsell’s designs in terms of their layout but they were longer and they looked rather different with a body profile comprising a smooth curve from the floor to the roof line of the carriage; they certainly complemented the look of the ACE with its new Bulleid locomotives. Another feature was the inclusion of more open saloons for third-class seating carriages together with the introduction of Bulleid’s novelty Tavern Cars in the 1948 winter timetable. Blood and custard liveried BR Mk1 vehicles started to appear on the south west section from 1951 so the ACE could be made up of both Bulleid (Malachite green) and Mk1 sets (blood and custard) for the different destinations. By 1962 all blood and custard Mk1 stock had been repainted in BR green for the last years of the ACE.

By late 1938 some of ACE’s south west section locomotive hauled Maunsell sets were repainted in the new light green or Malachite green livery. In September 1939 the ACE’s title immediately disappeared from timetables and a slower service with additional stops ensued. After the war years new Bulleid coach stock started to appear from early 1946 which transformed the ACE. These coaches were considered not to be radically different to Maunsell’s designs in terms of their layout but they were longer and they looked rather different with a body profile comprising a smooth curve from the floor to the roof line of the carriage; they certainly complemented the look of the ACE with its new Bulleid locomotives. Another feature was the inclusion of more open saloons for third-class seating carriages together with the introduction of Bulleid’s novelty Tavern Cars in the 1948 winter timetable. Blood and custard liveried BR Mk1 vehicles started to appear on the south west section from 1951 so the ACE could be made up of both Bulleid (Malachite green) and Mk1 sets (blood and custard) for the different destinations. By 1962 all blood and custard Mk1 stock had been repainted in BR green for the last years of the ACE.

Whilst the multi-portioned ACE was characterised by the inclusion of many brake coaches, Southern Railway never built its own full brake stock although it constructed many forms of covered carriage trucks (CCTs) and multi-purpose luggage vans for boat train work. In BR times this would change with the introduction of Mk1 coaches but such was the popularity of the ACE and other holiday services that ex LMS full brakes and six-wheeled Stoves were employed to accommodate the volumes of luggage on the sections out of Exeter. So whilst the ACE was uniquely green liveried from the mid-1950s the inclusion of BR maroon coloured brakes added a further dimension. Despite competition from other modes of transport this was still an extremely busy time for the ACE. Additional relief trains for summer weekend work had to be brought in to complement the phased section departures.

At times BR(S) south west division was really hard stretched to provide adequate relief trains for ACE services having to cope at the same time with the popularity of its Bournemouth and Weymouth holiday trains. The situation eased somewhat with the elimination of steam in Kent as many of the Battle of Britain Light Pacifics were transferred elsewhere within BR(S) territory; the Exmouth Junction (Exeter) shed receiving a significant number of locomotives. As a result large numbers of original Spam Can West Country/Battle of Britain class locomotives hauled services across the Withered Arm and on the Ilfracombe line until the end of steam. Even up until 1963 the ACE still had strong passenger demand with five separate departures from Waterloo. Spacious Bulleid corridor carriages and new Mk1 hauled sets would characterise the numerous departures which now included additional stops. The 10.15am Ilfracombe and Torrington portion would call at Templecombe, Seaton Junction and Barnstaple Junction before splitting coaches (for Torrington) and continuing all stations to Ilfracombe, the 10.35 Padstow and Bude service would call only at Axminster and Halwill Junctions then virtually all stations to Bude and to Padstow, a 10.45 portion would call at Lyme Regis and Seaton, the traditional 11.00 Torrington and Ilfracombe service calling at Sidmouth Junction, Eggesford and Barnstaple Junction before all stations to Ilfracombe and finally the 11.15 Plymouth, Padstow and Bude departure calling at Yeovil Junction, North Tawton and Okehampton (for Plymouth) before Padstow and a connection to Bude. Even in its last year of operation the Seaton and Lyme Regis departure was the only portion to be dropped.

At times BR(S) south west division was really hard stretched to provide adequate relief trains for ACE services having to cope at the same time with the popularity of its Bournemouth and Weymouth holiday trains. The situation eased somewhat with the elimination of steam in Kent as many of the Battle of Britain Light Pacifics were transferred elsewhere within BR(S) territory; the Exmouth Junction (Exeter) shed receiving a significant number of locomotives. As a result large numbers of original Spam Can West Country/Battle of Britain class locomotives hauled services across the Withered Arm and on the Ilfracombe line until the end of steam. Even up until 1963 the ACE still had strong passenger demand with five separate departures from Waterloo. Spacious Bulleid corridor carriages and new Mk1 hauled sets would characterise the numerous departures which now included additional stops. The 10.15am Ilfracombe and Torrington portion would call at Templecombe, Seaton Junction and Barnstaple Junction before splitting coaches (for Torrington) and continuing all stations to Ilfracombe, the 10.35 Padstow and Bude service would call only at Axminster and Halwill Junctions then virtually all stations to Bude and to Padstow, a 10.45 portion would call at Lyme Regis and Seaton, the traditional 11.00 Torrington and Ilfracombe service calling at Sidmouth Junction, Eggesford and Barnstaple Junction before all stations to Ilfracombe and finally the 11.15 Plymouth, Padstow and Bude departure calling at Yeovil Junction, North Tawton and Okehampton (for Plymouth) before Padstow and a connection to Bude. Even in its last year of operation the Seaton and Lyme Regis departure was the only portion to be dropped.

The ACE service was always characterised by innovation. By the late 1950s there were significant increases in car ownership and growing numbers of coach companies but travelling long distances was not easy. The motorway and major trunk road building programme was still in its infancy and for those that could afford it BR introduced a number of long-haul car carrying services such as the ‘Anglo-Scottish Car Carrier’ – these operations later rebranded as Motorail in 1966. The long West Country trek from London and the Home Counties was time consuming involving a considerable amount of effort and planning. Roads were not designed for significantly increased vehicle volumes and were often in a poor state of repair leading to the new phenomenon of the traffic jam. BR(S) countered and introduced a new car carrying section operating between Surbiton and Okehampton. This service was normally made up of eight CCTs together with a couple of coaches and a restaurant car as the Surbiton service had an 8.03am breakfast time departure time. It certainly portrayed a modern image of adventure as passengers watched their cars loaded on the CCTs and then boarding the carriages in the goods yard by way of step-ladders and not from the platform. The transportation of the motor car made this section of the ACE extremely heavy and was normally hauled by rebuilt Merchant Navy class locomotives such as no: 35017 Belgian Marine. For affluent passengers the ACE car carrier was attractive as the West Country could be reached from London in less than four and half hours. The delights of North Devon and Cornwall were then at passengers’ disposal as cars were driven off. Unfortunately, the West Country car carrying service was not to last. It operated for five summers between 1960 and 1964 but succumbed to competition as gradually roads and travelling time improved.

From its introduction until the end of steam, the image of the ACE was associated with a variety of locomotive classes. In 1918 LSWR had introduced the first of a new fleet of ‘King Arthur’ class locomotives to haul its West Country expresses from Waterloo. In these years the ACE as far as Exeter was dominated by the King Arthurs but by the end of the 1920s the more powerful ‘Lord Nelson’ class was available but it was to be a few more years until the new crack locomotives took over on a regular basis.

In Southern Railway times book photographic evidence record a number of King Arthur, Nelson and Merchant Navy class locomotives hauling the ACE on the down and up lines to Exeter with no: 453 King Arthur, no: 451 Sir Lamorak, no: 457 Sir Bedivere, no: 775 Sir Agrivaine, no: 788 Sir Urre of the Mount, no: 857 Lord Howe and no: 21C5 Canadian Pacific. These engines would run without stopping to Salisbury in 90 minutes where locomotives would be changed with a further non-stop run to Exeter. During the war years Arthur and Nelson class locomotives continued to provide the motive power for West Country trains (although journey times lengthened due to wartime restrictions) before the newer and more powerful Merchant Navy class were drafted on to the ACE service. These were closely followed by the slightly smaller West Country/Battle of Britain Pacifics which were to become mainstream locomotive designation. ACE designated locomotives would run non-stop to Salisbury (for water) and then on to Exeter Central and St Davids. Due to weight restrictions, routes beyond Exeter were served by the smaller West Country/Battle of Britain classes but the Waterloo – Salisbury – Exeter legs were mostly operated by the fast and elegant looking Merchant Navies – a locomotive class well versed to hauling the country’s heaviest trains such as Night Ferry. During the interchange trials a number of ‘foreign’ locomotives were used to haul the ACE including LNER A4s, LMS Pacifics and a rebuilt Royal Scot locomotive. In 1953 Merchant Navy classes across BR(S) were temporarily withdrawn with Britannias taking over the Waterloo to Exeter sections.

In Southern Railway times book photographic evidence record a number of King Arthur, Nelson and Merchant Navy class locomotives hauling the ACE on the down and up lines to Exeter with no: 453 King Arthur, no: 451 Sir Lamorak, no: 457 Sir Bedivere, no: 775 Sir Agrivaine, no: 788 Sir Urre of the Mount, no: 857 Lord Howe and no: 21C5 Canadian Pacific. These engines would run without stopping to Salisbury in 90 minutes where locomotives would be changed with a further non-stop run to Exeter. During the war years Arthur and Nelson class locomotives continued to provide the motive power for West Country trains (although journey times lengthened due to wartime restrictions) before the newer and more powerful Merchant Navy class were drafted on to the ACE service. These were closely followed by the slightly smaller West Country/Battle of Britain Pacifics which were to become mainstream locomotive designation. ACE designated locomotives would run non-stop to Salisbury (for water) and then on to Exeter Central and St Davids. Due to weight restrictions, routes beyond Exeter were served by the smaller West Country/Battle of Britain classes but the Waterloo – Salisbury – Exeter legs were mostly operated by the fast and elegant looking Merchant Navies – a locomotive class well versed to hauling the country’s heaviest trains such as Night Ferry. During the interchange trials a number of ‘foreign’ locomotives were used to haul the ACE including LNER A4s, LMS Pacifics and a rebuilt Royal Scot locomotive. In 1953 Merchant Navy classes across BR(S) were temporarily withdrawn with Britannias taking over the Waterloo to Exeter sections.

On 6 October 1947 the ACE first operated with a locomotive headboard attached to the buffer beams of newly painted Southern Railway Malachite green Merchant Navy classes. Into BR days the ACE locomotive headboard became a permanent fixture with a number of variations used but with a standard fixing across the smokebox door of the locomotive. The ACE named train from 1948 to 1951 was a colourful affair with a mixture of Malachite green and Brunswick green liveried West Country/Battle of Britain locomotives whilst some of the Merchant Navy classes were painted in the short-lived BR blue livery before being repainted in Brunswick green. In early BR times the ACE down line to Exeter included no: 35001 Channel Packet, no: 35010 Blue Star and no: 35029 Ellerman Lines hauling a mixture of Malachite green and blood and custard stock.

In later BR days modified or rebuilt Merchant Navy locomotives presented a more orthodox appearance to the express service. Nos: 35013 Blue Funnel, 35014 Nederland Line, 35020 Bibby Line, 35025 Brocklebank Line, 35029 Ellerman Lines and 35030 Elder Dempster Lines were seen rostered to the ACE. In BR days in and around Devon this included nos: 34015 Exmouth, 34022 Exmoor, 34054 Lord Beaverbrook, 34109 Sir Trafford Leigh Mallory, 35003 Royal Mail, 35017 Belgian Marine, 35030 Elder Dempster Lines, 35024 East Asiatic Company, 35010 Blue Star, 34072 257 Squadron and rebuilt Merchant Navy 35026 Lamport & Holt Line for Ilfracombe.

In later BR days modified or rebuilt Merchant Navy locomotives presented a more orthodox appearance to the express service. Nos: 35013 Blue Funnel, 35014 Nederland Line, 35020 Bibby Line, 35025 Brocklebank Line, 35029 Ellerman Lines and 35030 Elder Dempster Lines were seen rostered to the ACE. In BR days in and around Devon this included nos: 34015 Exmouth, 34022 Exmoor, 34054 Lord Beaverbrook, 34109 Sir Trafford Leigh Mallory, 35003 Royal Mail, 35017 Belgian Marine, 35030 Elder Dempster Lines, 35024 East Asiatic Company, 35010 Blue Star, 34072 257 Squadron and rebuilt Merchant Navy 35026 Lamport & Holt Line for Ilfracombe.

It was not unusual for smaller tank locomotives to complete the last leg of the ACE journey to North Devon. M7s nos: 30251 and 30255 could be seen pulling the four-coach Torrington portion alongside the quay at Fremlington although by the 1950s BR standard 2-6-4 tank locomotives started to replace the ageing M7s. In Cornwall un-rebuilt Spam Cans frequently hauled the final three or four coach section of the ACE to its end destinations. This would have included nos: 34079 141 Squadron and 34066 Spitfire for the Okehampton and Wadebridge sections, 34058 Sir Frederick Pile, 34070 Manston, 34075, 264 Squadron and rebuilt 34026 Yes Tor for the Halwill Junction to Padstow section. No: 34066 Spitfire was based specifically for Cornish operations and was frequently photographed in colour many times providing the rural sections of the ACE in the years up to ending of the dedicated service. Western Region diesel hydraulic locomotives took over ACE traction for the remaining year of life: The headboards that so defined the post war ACE were also removed – diesels nos: D7100 and D7097 that worked the Ilfracombe leg now looked so anonymous.

So on 5 September 1964 the train that in its heyday had carried more through portions to more destinations than any other train in the country was gone. Likewise, the motive power shed at Exmouth Junction was closed as all remaining services west of Exeter became diesel-operated. And so too, the lines to the rural idylls of the Withered Arm were unceremoniously lopped off by Beeching’s axe – the Padstow and Bude (North Cornwall) branches in 1966, Okehampton to Plymouth in 1968 and finally the Barnstaple to Ilfracombe branch in 1970.

For further information see the West Country Allure chapter in Luxury Railway Travel: A Social and Business History by Martyn Pring.

Shamrock Trains is a provider of 0 Gauge ready-to-run model railways and similar associated products. We provide a high quality, professional and personalised service to our customers. We are a highly knowledgeable operation providing specialist advice to customers around the world; we believe we are one of the few model railway retailers to operate in this way. Honesty, integrity, providing value for money and the highest level of customer care are the principles of our business.

Email us at enquiries@shamrocktrains.com, or phone us on 07759 310098.