Channel ports had been linked by rail on both sides of the water since the 1840s but a journey between London and Paris would have taken the best part of a half a day in the mid-19th century. Better propelled and faster steamers together with speedier trains operated by the South Eastern Railway (SER) and London, Chatham & Dover Railway (LCDR) – ultimately leading to the formation of the SECR management committee in 1899 – had cut this almost in half in the years before WWI. The twenty-one miles between Dover and Calais had been used for rapid boat trains since the late 1880s but the destination was reached by two competing routes each originating from different London stations and with different railway companies but converging at Admiralty Pier. Post-war SECR boat trains used the old SER route and the LCDR part of London Victoria station becoming the preferred starting point since there were longer platforms. When the Southern Railway was formed in 1921 it was logical for them to base their south east boat train/ferry operations at Dover as the Straights provided the shortest cross-channel crossing to the Continent. The Southern also consolidated their London-based boat train operations at the Victoria terminus – the station able to provide up to seven weekday services linking Britain and France. In this period the Southern also had other south east cross-channel routes from Folkestone-Boulogne and Newhaven-Dieppe and western channel crossings from Southampton.

Elite train services (Club trains) linking London to Paris via Dover and Calais were introduced by both the SER and LCDR in 1889 to coincide with the Paris International Exhibition. The Club trains had luxury American-style saloons and fourgons supplied provided by Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits (CIWL) – also known as Wagon-Lits – but these services were withdrawn on 30th September 1893 as they were not a commercial success due to the two railways’ competing offers and somewhat primitive maritime facilities at Dover. CIWL regrouped to mainland Europe but the precedent had been set to utilise luxury Pullman carriages in boat train formations dictated by a growing market by the end of the 19th century. SECR had run their own crimson-lake (maroon) liveried Pullman boat expresses hauled by rebuilt 4-4-0 E1 class locomotives in the years around grouping but these were older Pullman stock that had seen better days. There were demands for more luxurious cross-channel boat train services particularly as embarkation points became overcrowded. It was time for the newly-formed Southern to respond.

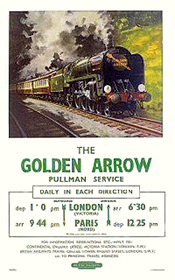

Southern Railway’s general manager Sir Herbert Walker had glimpsed the future of the inter-war luxury train when meeting Davison Dalziel, chairman of the CIWL management committee in Calais on 9 December 1922. This was the inauguration of the glamorous Calais-Méditerranée Express, better known as Le Train Bleu – the Blue Train. CIWL had thrown down the gauntlet but it was up to Southern and the Pullman Company (who enjoyed a close working relationship with CIWL) to create a similar first-class offer that would cater for an increasingly discriminating market particularly high-spending American tourists who were rediscovering their European roots. In 1924 Southern’s interim measure was the introduction of its first all-Pullman boat train known as ‘the White Pullman’ which ran from Victoria to Dover. This Pullman service had the new standard umber and pale cream livery which had been introduced earlier on the London-Brighton Southern Belle and was the precursor for CIWL’s first-class Pullman boat train between Calais and Paris – La Flèche d’Or or the Golden Arrow. Southern refrained from adopting the Golden Arrow title at the time until it had finalised its own plans. Whilst Pullmans once again graced Dover Marine Continental passenger terminal, Southern railway’s astute management team was devising an integrated luxury train product and offer that would be sufficiently distinctive and set the world talking. This came on 15th May 1929 with the full launch of the London-Paris Golden Arrow.

Southern Railway’s general manager Sir Herbert Walker had glimpsed the future of the inter-war luxury train when meeting Davison Dalziel, chairman of the CIWL management committee in Calais on 9 December 1922. This was the inauguration of the glamorous Calais-Méditerranée Express, better known as Le Train Bleu – the Blue Train. CIWL had thrown down the gauntlet but it was up to Southern and the Pullman Company (who enjoyed a close working relationship with CIWL) to create a similar first-class offer that would cater for an increasingly discriminating market particularly high-spending American tourists who were rediscovering their European roots. In 1924 Southern’s interim measure was the introduction of its first all-Pullman boat train known as ‘the White Pullman’ which ran from Victoria to Dover. This Pullman service had the new standard umber and pale cream livery which had been introduced earlier on the London-Brighton Southern Belle and was the precursor for CIWL’s first-class Pullman boat train between Calais and Paris – La Flèche d’Or or the Golden Arrow. Southern refrained from adopting the Golden Arrow title at the time until it had finalised its own plans. Whilst Pullmans once again graced Dover Marine Continental passenger terminal, Southern railway’s astute management team was devising an integrated luxury train product and offer that would be sufficiently distinctive and set the world talking. This came on 15th May 1929 with the full launch of the London-Paris Golden Arrow.

In a short period of time aided by smart marketing and promotion the combined Golden Arrow/Flèche d’Or service (a product of two railway companies – the Southern and Nord) became one of the world’s best known luxury trains. The train/boat/train service had its own dedicated first-class only steamer crossing the channel between Dover and Calais – the TSS Canterbury being the pride of Southern Railway’s fleet. In July 1930 the Golden Arrow was appointed with eight renovated umber and cream art deco Pullman cars Adrian, Diamond, Ibis, Lady Dalziel, Lydia, Onyx, Pearl and Princess Elizabeth. The exotic Golden Arrow became famous for its personalised service and haute cuisine menus frequented by society’s well-heeled classes.

The rather grandiose start unfortunately was not to last as darkening economic clouds downgraded the Golden Arrow from its exclusive first-class Pullman status. The train then accommodating first and second-class passengers together with Pullman first-class passengers. Conditions on the Continent were no better forcing the French to make a similar response to their CIWL Pullman operation. Cross-channel passenger traffic plummeted with total journeys taken nearly halving in 1932 against a long-trend average of 1.5m over the years 1925 to 1930. In the period 1933 to 1935 a recovery recommenced to an average 1.125m passengers per annum crossing the channel by train/boat/train. By the summer of 1937 the number of continental passengers had recovered to the long-term trend with Saturday 31st July experiencing an all-time high of 22,828 passengers for the day – requiring some 50 additional boat train workings. Until recovery the look and composition of the multi-class Golden Arrow changed typically made up of three to four (or more) Pullman coaches located in the middle of the train with one or more luggage trucks and general utility vans at one end with a mix of ordinary coaches at the other end. In 1938 the Maunsell first-class rake was upgraded and renovated with new upholstery and sported a new Southern Railway Olive green livery. Four of the Lord Nelson locomotives regularly used on the service were also repainted in Olive green providing the Golden Arrow with a much-needed facelift.

Post-war Southern Railway made strenuous efforts to run a luxury train service again making the Golden Arrow a first and second-class all-Pullman service whilst running a separate train to carry other first and second-class passengers. A ‘golden arrow’ insignia was carried on locomotive sides, a specially devised headboard together with Anglo-French flags. This promotional initiative coincided with the deployment of the new dedicated Golden Arrow steamer Invicta. The all-Pullman Golden Arrow was now made up of ten coaches with three second-class Pullmans – two parlours cars and a brake parlour – being converted and renumbered together with three first-class kitchen cars, two parlour cars, a brake parlour and a new product innovation – the Trianon Bar car. The ideas for a dedicated bar car had stemmed from CIWL’s luxury Blue Train French Riviera service but also led to BR(S) later experimenting by creating a ‘tavern coach’ made up of new Bulleid stock used on many longer-distance commuter services. In May 1947 Golden Arrow was made a first-class Pullman service only but the composition again changed in October 1949 when second-class Pullmans were reintroduced.

On 11 June 1951 coinciding with the Festival of Britain celebrations the Golden Arrow received another significant make-over with the introduction of seven newly built first-class Pullman cars (being part of a suspended pre-war order) and three rebuilt second-class cars making Golden Arrow a truly luxurious train again headed by new Britannia class locomotives. There were some minor changes to the Pullman composition but the overall ten car provision continued throughout the 1950s. This period was really the pinnacle of the Golden Arrow but it was not to last because of regular and reliable air services between Britain and the Continent and the increasing fashion to take the car to France on roll-on roll-off ferries – many ironically operated by BR. These changes in consumer choice started to nibble away at the edges of the luxury train service.

Throughout its operational life the Golden Arrow luxury boat train was serviced by just two cross-channel steamships – the TSS Canterbury delivered in 1929 and its replacement SS Invicta in 1940. The Invicta launched in 1939 was not fully fitted out and was pressed immediately into war-time duties not commencing life as the dedicated Golden Arrow ship until mid-October 1946 when she took over the sea crossing from TSS Canterbury.

The Southern’s Docks and Maritime Committee were first briefed as a proposal by the general manager at a meeting on 25 January 1928 where he gave intention for the company to introduce an additional steamer to supplement the new Golden Arrow service between London and Paris via Dover and Calais. Southern did not hang around with the commissioning process for the steamer. The ship christened TSS Canterbury was built by Wm. Denny & Bros. Ltd at Dumbarton and launched on 13 December 1928 at a contract price of £220,225. She had a capacity for 1,400 passengers but as she was planned as a special steamer she started life catering for up to 300 de-luxe first-class Golden Arrow travellers who would pay a special £5 inclusive fare covering fare, reserved Pullman seats and supplements. As a single-class ferry TSS Canterbury provided exceptionally spacious surroundings for the short journey across the Dover Straights. Up-scale facilities included a 100 cover dining saloon on the main deck, private deck cabins and a garden lounge as well as screened alcoves all finished in a ‘warm cream’ décor.

In 1932 when she was converted to a two class vessel and despite the change Canterbury still maintained her own distinctive atmosphere as a turbine steamer. With a broader customer base the revised on-board facilities provided meals, drinks and gifts in the ship’s restaurants, bars and duty free shops; these were highly valued by Southern as a source to generate additional profitable revenue streams. As the vessel was the dedicated Golden Arrow service she was always immaculately maintained by the ship’s single crew. For a while in the mid-1930s the ship was only covering one leg of the Golden Arrow service any one day due to routing changes via Folkestone. Following the war TSS Canterbury reintroduced the Golden Arrow service on 16 April 1946. Once she was displaced by Invicta the vessel continued to provide many years of service and was used principally on the Folkestone-Boulogne service until she was laid-up in September 1964. The following July TSS Canterbury was towed away for breaking-up.

Invicta, similarly as TSS Canterbury, was built by Wm. Denny & Bros. Ltd and launched on 14 December 1939. She, too, had a passenger capacity of 1,400 passengers but was only converted to full operational service after WW2. Invicta however, became a key marketing tool used in Southern and early British Railways inspired promotional films, posters and advertising for the Golden Arrow service in the late 1940s and 1950s. The vessel had a long-service life associated with the Golden Arrow. She made her final trip on 8 August 1972 (the month before the final journey of the Golden Arrow) and was then laid-up at Newhaven until she was towed away for scrapping in the Netherlands in September of that year.

In the early years the Golden Arrow was normally hauled by Stewarts Lane based 4-6-0 Lord Nelson class locomotives but also with the similar but slightly less powerful King Arthur class. Both locomotive classes were also used for the increasing traffic to and out of Southampton Docks for ocean liner boat trains. In the ten years before WWII Lord Nelson and King Arthur classes became the backbone of the Golden Arrow service. Post-war the Golden Arrow was hauled by more powerful air-smoothed 4-6-2 Merchant Navy Pacific class locomotives – each one named after shipping lines. The Merchant Navies in their resplendent new Malachite green liveries were soon to become regulars – the post-war inaugural run headed by the appropriately named no: 21C1 Channel Packet.

In the early years the Golden Arrow was normally hauled by Stewarts Lane based 4-6-0 Lord Nelson class locomotives but also with the similar but slightly less powerful King Arthur class. Both locomotive classes were also used for the increasing traffic to and out of Southampton Docks for ocean liner boat trains. In the ten years before WWII Lord Nelson and King Arthur classes became the backbone of the Golden Arrow service. Post-war the Golden Arrow was hauled by more powerful air-smoothed 4-6-2 Merchant Navy Pacific class locomotives – each one named after shipping lines. The Merchant Navies in their resplendent new Malachite green liveries were soon to become regulars – the post-war inaugural run headed by the appropriately named no: 21C1 Channel Packet.

In a few weeks the Golden Arrow would be joined by Stewarts Lane based, but at the time unnamed, 4-6-2 light Pacifics which were later classified as the combined West Country and Battle of Britain classes; they became a familiar site on the service. Following the Festival of Britain in 1951 Golden Arrow was hauled by the new generation of British Rail Brunswick green liveried 4-6-2 Britannia class Pacifics. The locomotives were no: 70004 William Shakespeare and no: 70014 Iron Duke who would also work the other prestigious boat train the Night Ferry service. The combination of the newly introduced Pullman stock and the Britannias provided powerful images of the Golden Arrow luxury train service which were used extensively by BR for promotional purposes.

These combinations of locomotives remained unaltered until full electrification took over as the motive power. Due to the extensive electrification work taking place in south east England BR(S) experimented with diesel-electric traction. In the mid-1950s for two short periods on the Golden Arrow former Southern diesel-electric locomotives no: 10202 and 10203 were used to haul the Arrow both ways. With electrification came frequent disruption problems and with heavy loads the Golden Arrow would also result to haulage by the larger rebuilt Merchant Navy 4-6-2s with 6,000 gallon tenders. The last steam hauled Golden Arrow was on 11 June 1961 conveyed by no: 34100 Appledore and thus ended an iconic period of steam traction which had been such an instrumental feature of the Golden Arrow’s image. Class 71 electric locomotives were built for non-multiple unit trains like Golden Arrow and Night Ferry. The E5000 class locomotives took over the following day.

These combinations of locomotives remained unaltered until full electrification took over as the motive power. Due to the extensive electrification work taking place in south east England BR(S) experimented with diesel-electric traction. In the mid-1950s for two short periods on the Golden Arrow former Southern diesel-electric locomotives no: 10202 and 10203 were used to haul the Arrow both ways. With electrification came frequent disruption problems and with heavy loads the Golden Arrow would also result to haulage by the larger rebuilt Merchant Navy 4-6-2s with 6,000 gallon tenders. The last steam hauled Golden Arrow was on 11 June 1961 conveyed by no: 34100 Appledore and thus ended an iconic period of steam traction which had been such an instrumental feature of the Golden Arrow’s image. Class 71 electric locomotives were built for non-multiple unit trains like Golden Arrow and Night Ferry. The E5000 class locomotives took over the following day.

The French had been running their counterpart Calais to Paris express Pullman service (La Flèche d’Or) since September 1926. In this period the Flèche d’Or was made up of ten CIWL chocolate and cream Pullman cars (Voiture Salon Pullman) displaying the arrows of gold painted on the coach sides. The Pullman coach liveries later changed to the more familiar blue and cream in the early 1930s. The Pullman carriages for the Flèche d’Or bore the name-plate of British coach manufacturer – the Leeds Forge Company – who had built the glamorous stock for the Calais-Méditerranée Express, better known as Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) several years earlier. The Flèche d’Or had a capacity of 300 first-class passengers who were transported to Gare du Nord in the most luxurious fashion possible at the additional cost of approximately 13s. 6d (£0.68p).

The steel-sided French Pullman coaches – assembled in pairs or couplages – were longer in length 77’ buffer to buffer with a maximum width of 9’ 7”. A feature of these coaches was that they incorporate their own kitchen so that passengers may be served with meals in their seats without having to adjoin to the dining car. The train would be waiting alongside the quay in Calais to facilitate a quick transfer of passengers from ship to train. Another unusual feature of the Flèche d’Or was the luggage brake. The French brake had a middle section which looked like a bird caged van but had two detachable containers or sealed luggage boxes on either side. Sometimes a train formation would include two of these luggage vans. These would contain the passenger’s luggage which would be loaded at London Victoria together with any other important freight items and documents. This would also include ‘registered’ baggage that could clear and cross frontiers without customs examination until it reached its final destination where it would be thoroughly examined.

The arrangement on the English side would be slightly different as the low loading truck would carry a row of the containers fastened securely with chains and hauled at the rear of the train. At Dover Harbour these containers would be unchained, taken off and loaded on to the steamer; once at Calais they would be winched off again and rapidly loaded on to the special French luggage van without passengers having to deal with French customs at the port. This process enabled a quick get-away of the eleven carriage in total train to Paris which, if full, would weigh in excess of 500 tons.

When the Golden Arrow/Flèche d’Or lost its exclusive first-class Pullman preserve in the early 1930s the make-up of the train changed to a multi-portioned luxury express (similar in concept to the Southern’s Atlantic Coast Express) as different onward train services and destinations had to be accommodated. A number of sleeping cars would be attached to the rear of the Flèche d’Or which was now made up of six Pullman cars. The sleeping cars would then form part of the celebrated Le Train Bleu and the Rome Express. On arriving at Paris du Nord the sleepers would then be worked around to Gare du Lyon and attached to the rest of first-class only Le Train Bleu bound for the French Riviera and the Rome Express which comprised both first and second-class sleepers. The Italian train would pass through the Mont Cenis Tunnel enroute to Turin, Genoa, Pisa and Rome. In busy summer periods at Calais the Paris-bound Pullman sleepers might form a complete second train together with a third Nord train for ordinary passengers – all three trains leaving one after another and making a non-stop run to the French capital and access to the rest of the greater European railway network.

In October 1935 there were again some changes in France as the Calais-Dover service was re-routed via Boulogne and Folkestone so that the CIWL Pullman cars could be used both ways. The Paris departure time was changed to allow more time for the empty Pullmans to be worked from Boulogne to Calais. Post-war the Flèche d’Or recommenced on 15 April 1946 made up of first-class Pullmans and SNCF first and second-class ordinary coaches. Journey times between Calais and Paris were rather long because of the state of the track but the French authorities put considerable efforts into improving the line and by the late 1940s mainline operations began to resemble pre-war running for Flèche d’Or. In the 1950s SNCF initiated their electrification plans for the railways in northern France.

Steam traction for Flèche d’Or was provided in both Nord and SNCF days by 4-6-2 (2-3-1E) Chapelon ‘Super-Pacific’ locomotives. These remained in service until full electrification of the line. For some time in the 1960s the Flèche d’Or would be headed by both steam and diesel-electric traction which necessitated a stop to change locomotives – the route between Amiens and Paris being turned over to electric traction. Throughout this period the powerful Chapelon steam locomotives also handled the Paris-Calais section of the Ferry Boat de Nuit. Steam was to last longer in France on both the Flèche d’Or and Ferry Boat de Nuit services. The last steam-hauled Flèche d’Or run was on 11 January 1969 with the CIWL Pullman cars being taken out of service at the end of May that year. On both sides of the channel the Golden Arrow became more utilitarian.

The Golden Arrow/Flèche d’Or was always deemed a luxury boat train service and for most of its operational life it was well supported by its railway masters on both sides of the water. Electrification changed the nature of the Golden Arrow as David St John Thomas and Patrick Whitehouse in their book ‘A century and a half of the Southern Railway’ comment “By the 1960s the variety of steam classes and the glamour of the Golden Arrow had given way to the dull but efficient monotony of electric working.” On the other hand electrification provided a speeded up service to the coast but the train had lost part of its personality. Second-class Pullmans were withdrawn in the 1960s. The Golden Arrow became a train of first-class Pullman stock and ordinary second-class coaches.

It was only in the final years that BR and SNCF began to view the service as anachronism and a relic of a bye gone age. In 1968 BR decided to give the Golden Arrow one final throw of the die with a livery change where the Pullman cars were repainted in corporate blue and grey. The Golden Arrow name on the lower blue panel replaced the coach name and class designation and car numbers appeared at coach ends. With this make-over the Pullman had lost its unique branding but customers (formally known in BR speak as passengers) found it difficult to differentiate the vehicles. A total of six Pullmans – two kitchen cars, three parlours and a parlour brake – formed part of the Golden Arrow which was hauled in its final years by blue liveried with full yellow ended E class locomotives.

In France the Flèche d’Or having lost its Pullman cars in 1969 suffered a similar fate of railway modernisation. In Britain the end of the Golden Arrow came on 30 September 1972; Continental travel would become less glamorous with its demise but the memory of the Golden Arrow as one of Britain’s most famous luxury and easily-recalled named-trains lives on.

For further information see the Great Cross-Channel Boat Train Expresses chapter in Boat Trains: The English Channel & Ocean Liner Specials by Martyn Pring.

Shamrock Trains is a provider of 0 Gauge ready-to-run model railways and similar associated products. We provide a high quality, professional and personalised service to our customers. We are a highly knowledgeable operation providing specialist advice to customers around the world; we believe we are one of the few model railway retailers to operate in this way. Honesty, integrity, providing value for money and the highest level of customer care are the principles of our business.

Email us at enquiries@shamrocktrains.com, or phone us on 07759 310098.