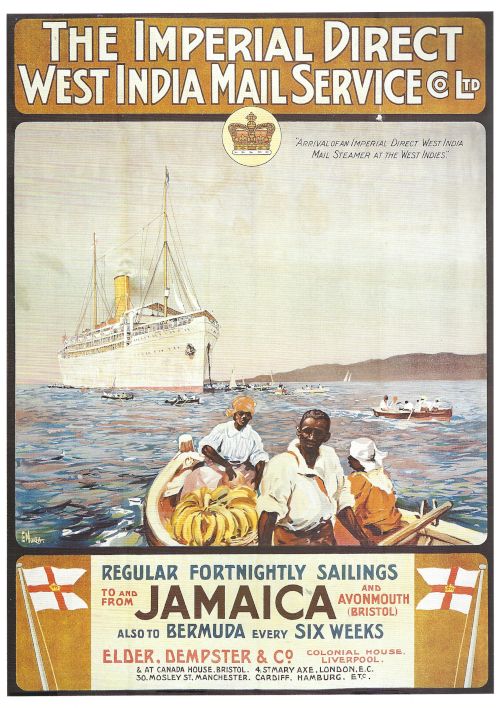

In mid-Victorian times when the Great Western struck out west from Paddington, Brunel’s mission purportedly was to link Bristol with New York. Despite the company’s best endeavours this never materialised as planned. The city remained an important commercial and maritime centre throughout the remainder of the 19th and throughout the 20th centuries, but Bristol never achieved the status of a major transatlantic liner port as originally envisioned to compete with Liverpool. It did, however, have a really good go at it. In 1901 with new port facilities constructed at Avonmouth, the GWR (and Midland Railway) tried to muscle in on increased passenger liner trade with emerging tourist markets in the West Indies and Central America. The white-hulled refrigerated hold cargo liners – better known as ‘banana boats’ – of the Imperial Direct Line and their West India Mail Service, and later the Elders & Fyffes ships, remained a feature of the Bristol Channel skyline until the late 1960s.

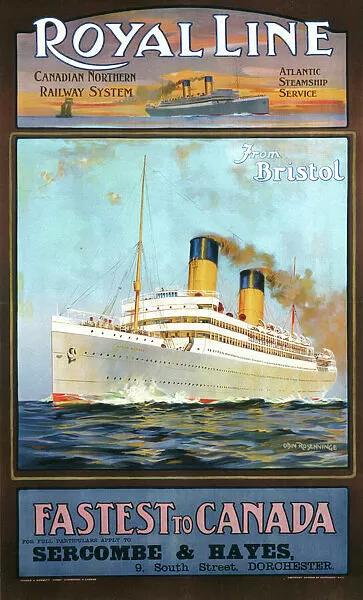

In July 1908 the new King Edward Dock was opened allowing the largest of steamers direct access straight into Avonmouth from the Bristol Channel. And with direct boat train access with a newly constructed railway terminal built alongside the dock complex, the vast interiors of Canada beckoned. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s major trans-continental competitor the Canadian National Railway System commenced a new Dominion bound passenger shipping operation known as the Royal Line with reconfigured liners from the Mediterranean, providing according to the company, the fastest Canadian water route. Despite being a successful operation it was not to last as the Great War intervened with one of their two vessels sunk, and the other ultimately acquired by Cunard. The company never achieved the momentum to compete with Canadian Pacific and Cunard’s new intermediate vessel operations of the 1920s.

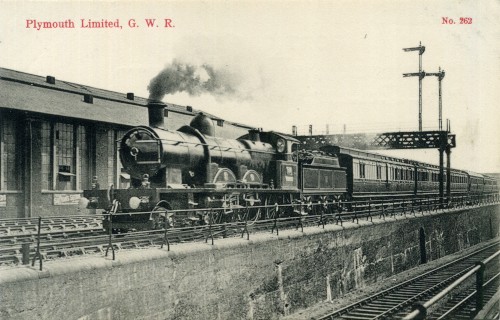

Despite Bristol’s best accomplishments, the focus headed west to Plymouth and a tale of intense competition between the GWR and LSWR towards the end of the 19th century. When the Great Western eventually won out, the story moved on with the company collaborating with some of the world’s biggest shipping lines. Plymouth became GWR’s ‘French Connection’ and a haven for the mail drop as part of a fast-developing passenger liner business. The GWR Ocean Mails and their accompanying boat trains became steadfast features of the city’s landscape for over a century.

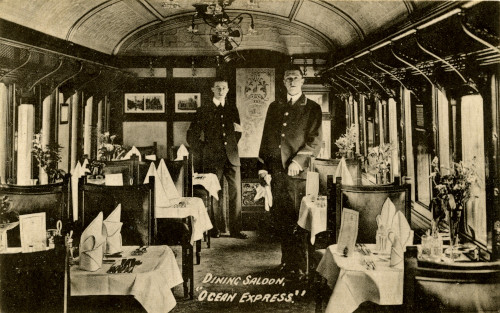

In 1919 Cunard moved its largest liners from Liverpool to Southampton; it marked the ascendency of the English Channel in the operation of the Atlantic Ferry. Whilst Southampton was a home port for a large proportion of the British liner fleet – views of giant passenger ships always dominated the city’s skyline – another western channel port was also kept pretty busy. Plymouth had emerged as the country’s major port of call; for the best part of a century, it was forever associated with the all-important mail drop as ships called from all corners of the globe and particularly from Australia, New Zealand, the Far East and India. And with significant growth in the volume of transatlantic traffic, Plymouth not only became an important dropping point for Britain’s merchant fleet, but also Continental steamers especially those of French and German shipping lines. With Plymouth additionally an Admiralty port, the route to and from Paddington was busy and fast benefiting from the construction of the new Westbury shortcut in the summer of 1906. The introduction of named train services was now par for the course, and with it the finest dining cars which were also used on the company’s Fishguard boat trains.

When the Great Western Railway launched its Historic Sites and Scenes of England 1904 travel book, it was unapologetically targeted at American visitors. According to The Sphere it was:

‘a most admirable specimen of how a railway company can best utilise its forces. This is no mere puff. It is a handsome volume of 128 pages, very elaborately illustrated with everything of interest that can be seen on the great railway’s excellently managed system. The writer has a keen sense of those literary and historic associations which appeal with full force to the American pilgrim.’ (1)

Wooing free spending American tourists was a key business imperative and from the early years of the 20th century firmly lodged in the Great Western’s agenda. The company also made ground-breaking moves investing in a New York representative office for the benefit of the city’s chattering classes who could choose to head to Europe almost at a moment’s notice. According to Dr Alan Bennett a move that cemented the company’s long-term reputation for working with the tourism trade in the United States. (2)

Hardly surprising such promotional efforts proved useful for British and Continental shipping lines alike. The Great Western actively went out of its way to court shipping management officials who all had substantial US offices to secure travel business. One Norddeutsche Lloyd (NDL) travel poster highlighted the company’s quartet of steamers showcasing one vessel leaving New York’s skyline behind, and all geared-up to land London bound passengers at Plymouth whisking them away with connecting special high-speed ocean liner trains. By 1906 Hamburg America Line’s (HAGAG) luxurious SS Amerika stopped regularly at Plymouth with a steady flow of affluent American visitors. Passengers heading to Britain were now more than willing to board one of the GWR’s tenders in Plymouth Sound and increasingly in significant numbers. The company’s famous Ocean Mails boat trains were now synonymous with prosperous tourists charging off to Paddington and able to reach London in under five hours. In the same year GWR inveigled a group of London based German journalists putting them on a special Plymouth train. The Clifton Society reported the party was entertained with a trip around the Sound on one of company’s tenders. No doubt company officials underlined the importance of new German transatlantic liners calling at the port on eastbound crossings! (3) Before the Great War HAPAG and NDL vessels on German bound journeys were consistently stopping off at Plymouth as well as the French ports of Cherbourg and Le Havre. For a while the port of Brest was also advanced as a French mail drop with the GWR highly involved with Plymouth-Brittany cross-channel summer tourist traffic.

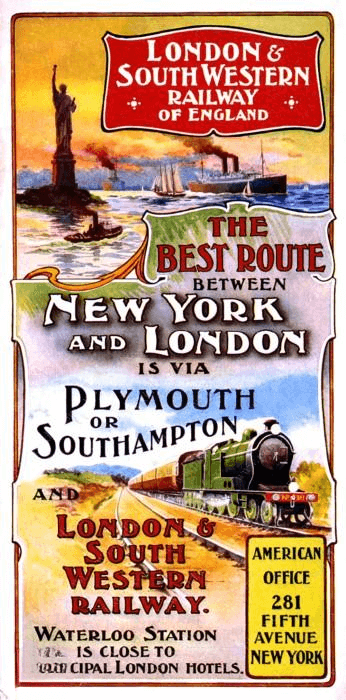

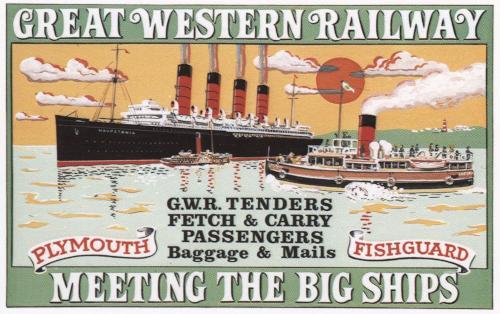

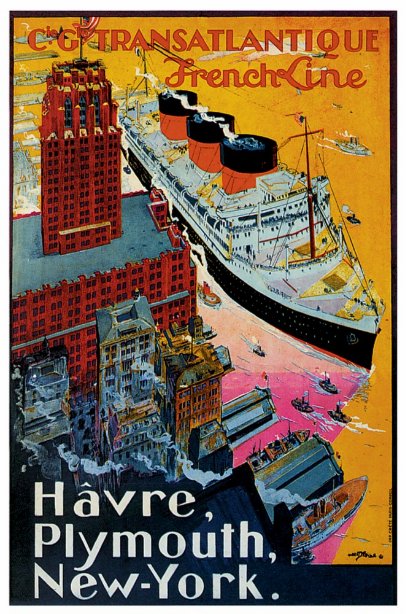

With Plymouth mail business increasing large numbers of steamers were dropping anchor in the Sound. From the 1890s this was something GWR’s arch-competitor to the south west, the London & South Western Railway (LSWR), was determined to grab a slice of lucrative ocean liner business as well as expanding its share of Breton cross-channel tourist and freight operations. Yet GWR not only owned the Millbay Docks entrance but had controlled the entire mainline from Paddington into the docks since 1878. The LSWR had an alternative Plymouth route via Salisbury and Exeter but had to make separate arrangements for harbourside access. The decision to invest in new facilities came about as the result of the new American Lines US mail franchise (which moved from Liverpool to Southampton) as well as additional Continental steamer business. Expanding routes to Central and South America merely added to port activity. By this time Dutch passenger ships were highly visible, and Germany’s liners had become luxury beacons of first-class travel and seriously rivalling Cunard and White Star’s floating palaces. The French were a little later off the mark with their first four funnel grand steamer France making its maiden voyage just a week after Titanic’s departure.

Ships heading to the other side of the world were also pretty well-appointed with P&O and Orient Line the major British operators predominantly painted in white (Orient Lines ships had corn-coloured hulls) to reflect the heat. The phrase ‘posh’ (port out, starboard home) dates from this period and is forever associated with a more comfortable Indian and Far East sea passage, although there is now academic debate about its authenticity. However, what is not a matter of conjecture was the necessity of firms pandering to the needs of Edwardian upper-class travellers who enjoyed smart, stylish and lavish lifestyles; they were always high on railway company and shipping lines’ travel agendas. P&O and Orient Line operated out of a number of London docks until Tilbury was constructed with the Plymouth call offering the chance to board liners with the mail for a slightly later departure. Likewise, in reverse Plymouth also allowed passengers to disembark with mail. By 1901 this was a highly organised affair; GWR and LSWR timetables were built into Orient Line’s brochures. But despite LSWR’s best endeavours in 1910 the Great Western saw off the Stonehouse challenge; the company regrouped to Southampton and the port they had owned since 1892. GWR, on the other hand, quietly got on with mail and passenger business running fast and efficient on demand boat train services only to be interrupted by the Great War.

Post-war the mood music changed for the better. Transatlantic passenger business was brisk as Americans flocked to Britain and Europe as soon as the Versailles handshaking and photocalls were completed. By the early 1920s Plymouth became a much-desired dropping point for ‘cash rich – time poor’ American visitors who wanted to get to London for either business or leisure purposes as quickly as possible: For many US plutocrats, no doubt a combination of both since Plymouth had always registered with American tourists.

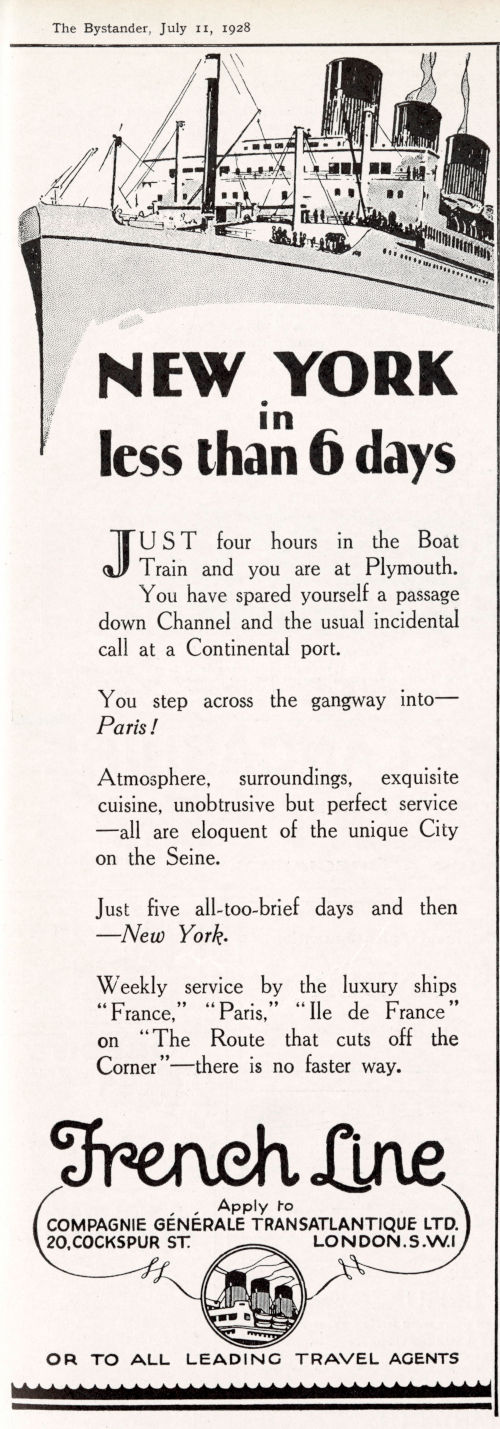

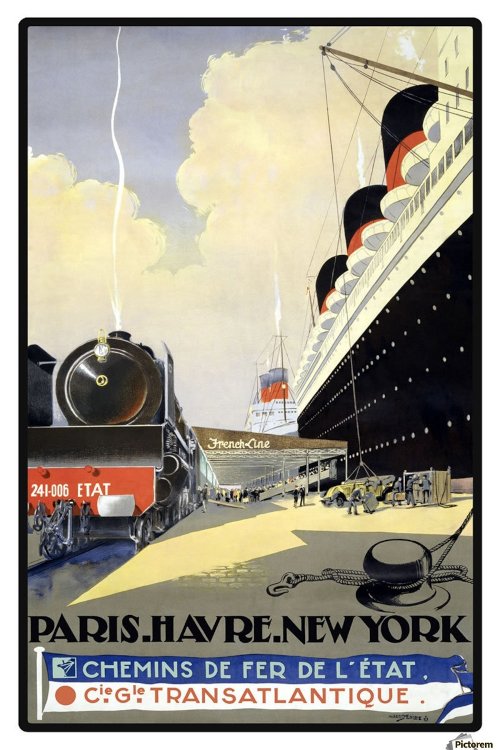

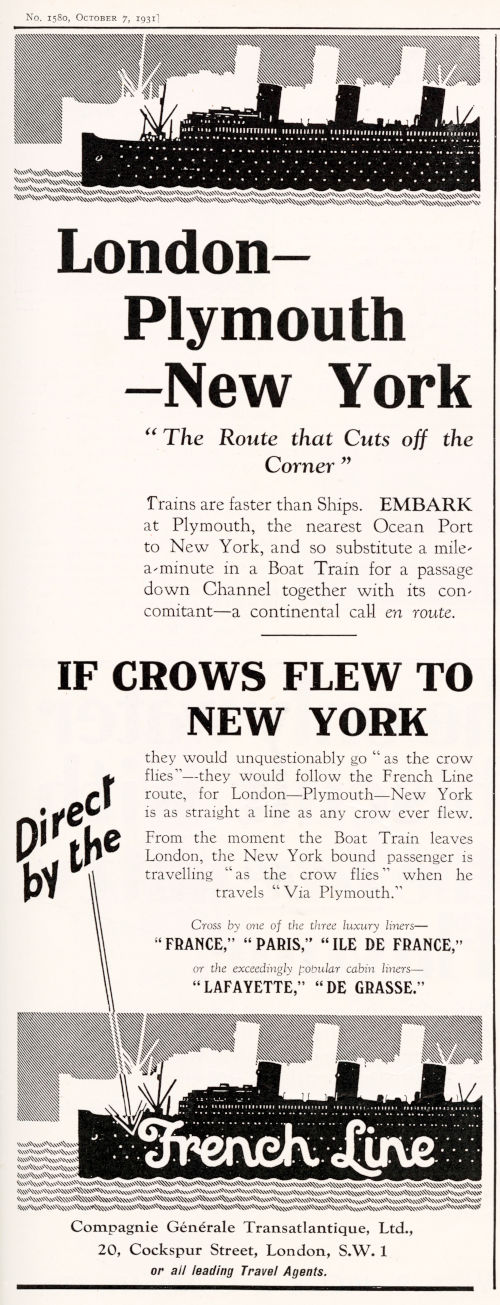

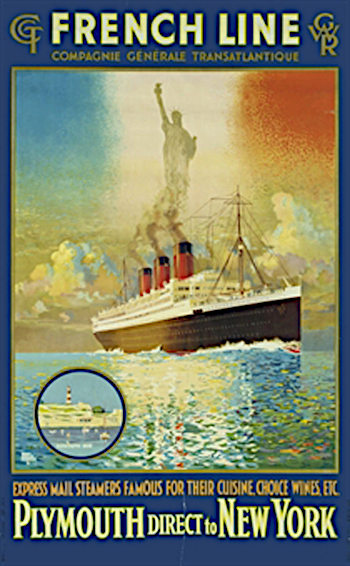

The new decade introduced a golden era for steam hauled railway travel and particularly for Plymouth liner workings. Ocean steamers reigned supreme whether for line-voyages or a fast-growing cruise market. But with prohibition enacted into Federal Law, Americans in their droves turned to British, French and other European nation shipping lines. Germany’s three largest liners were requisitioned for war-time losses and remaining ships were essentially out of favour until the late 1920s. And there was no point in crossing the Atlantic for the best part of a week without a drink and it was to the flamboyant French that many affluent US citizens turned to. After all, crossing the pond was one of life’s celebrations. As a result, the Great Western really upped the ante for liners stopping at Plymouth which, depending on vessel, could save six hours or more over Southampton steaming time. Thus, began a close working relationship with CGT French Line which lasted well into the British Railways era. Paddington international boat train arrival and departures was now a real alternative to their Southampton-Waterloo rivals. GWR was far in advance of its Big Four rail partners in advancing the American cause, even going to the extent of proposing the establishment of ‘railway offices on board transatlantic liners for the advanced distribution of promotional literature, itineraries and railway tickets en route.’ (4)

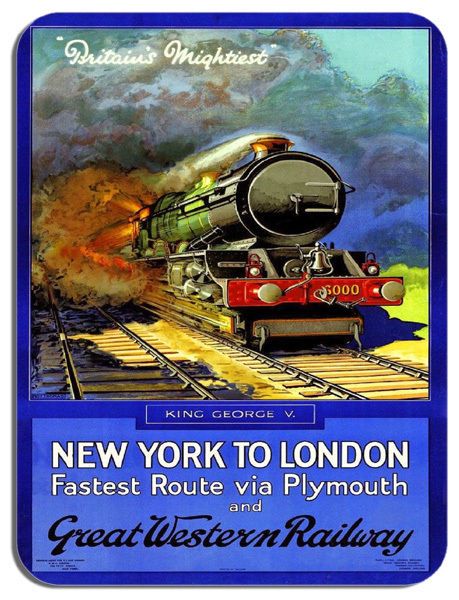

CGT French Line had a terrific fleet of liners offering high-quality culinary provision guaranteeing a premier class experience with a format designed to attract American travellers who did not take to US-owned vessels caught up with alcohol prohibition. French liners were plush and exciting; the grandly fashioned L’Atlantique was very much in the stylistic visions of the Île de France as well their express liners Paris and France designed to cut Atlantic Ferry crossing times. By 1928 the Great Western and CGT French Line were carefully coordinating marketing activity. They not only cultivated the American market, but with selective advertising in upscale ‘illustrated weekly’ titles such as Bystander and The Tatler offered British travellers an alternative with a slice of Paris on New York voyages with both east and west-bound crossings. In the inter-war years Plymouth’s port of call business was huge. CGT French Line, and increasingly other European shipping firms, dropped off in the Sound those international travellers requiring London before progressing to other Continental destinations with the balance of passengers. With Plymouth passenger disembarking up to three separate GWR relief boat trains per ship were sometimes required. Restaurant car express boat trains, hauled by powerful Castle and/or King Class locomotives, were quick as Paddington could now be reached in four hours and ahead of time of the best LMS Liverpool boat expresses.

Plymouth landings historically were convenience rather than luxury led, but from the mid-1920s there was a rapid change of thinking by the Great Western. The company had tasted the coffee and now had a clear intention of catering for a burgeoning first-class passenger market. Certainly, the relationship with CGT French Line was a case in point; east-bound crossings with a Plymouth drop point and continuation to Le Havre with its awaiting Paris ETAT boat trains was a hugely successful arrangement. In 1929 GWR introduced seven Pullman cars for its prestige Plymouth ocean liner workings producing dedicated promotional brochures and advertising extolling the Southampton alternative. Two years later the company dropped the Pullman association by launching its own equivalent high-quality Super Saloon carriage stock named after immediate Royal family members. GWR with its Plymouth boat trains could now tap into America’s nouveau-riche used to comfort, quality, service, and most importantly speed which for businessmen and fellow travellers on a tight visiting schedule was met with typical Great Western flair.

The close-working relationship with CGT French Line was evident with dedicated liner named coach boards produced for the Super Saloons. Yet the move into the luxury first-class segment was not as successful as anticipated as transatlantic passenger demand faltered considerably with the early 1930s depression years, and a reluctance amongst even the most well-to-do passengers to pay a Pullman style travel supplement. But by mid-decade a degree of normality returned to travel. Despite Southampton’s increasing prominence as a home port, the Great Western with their Plymouth stopover still maintained a pretty prestigious niche with CGT French Lines who had London offices in Cockspur Street as well as in Manhattan. When their luxurious liner Normandie came on stream in May 1935, the vessel was the largest and fastest ship afloat crossing the pond in just over four days. The grand voyages of Normandie, described as the most beautiful ship in the world, was centre stage of just about every piece of promotional literature and written into folklore. Many Americans simply loved the ship although she was not as successful commercially as Cunard’s Queen Mary.

The focus by the end of the decade changed somewhat as GWR boat trains became mail trains with passenger accommodation rather than deluxe passenger trains that carried mail. New super-liners on the Atlantic Ferry were faster eroding some of the premium of stepping ashore early at Plymouth. Many passengers on British ships (and especially Queen Mary) were content to stay on board and disembark later at Southampton where they would be met by boat trains with Pullman stock introduced by the Southern Railway as a result of the Great Western ironically handing back their Pullmans. Despite market changes Plymouth boat train activity nonetheless remained extremely busy up until the outbreak of war again in September 1939.

Plymouth’s position as the nation’s leading port of call, however, was about to change post-war as the new nationalised railway organisation saw no reason to provide competing boat trains to Millbay. Cunard, P&O and Orient (who merged in 1960), United States Lines and other smaller firms began withdrawing their Plymouth stops leaving Southampton as the premier port. This left old friend CGT French Line as the only pre-war shipping line to continue using the port. Unfortunately, this was all to end in 1963 as British Railways Western Region pulled the plug on all south west boat train operations as the jet liner now reigned supreme over the Atlantic. Over one hundred years of combined mail and boat train operation was consigned to history.

Shamrock Trains is a provider of 0 Gauge ready-to-run model railways and similar associated products. We provide a high quality, professional and personalised service to our customers. We are a highly knowledgeable operation providing specialist advice to customers around the world; we believe we are one of the few model railway retailers to operate in this way. Honesty, integrity, providing value for money and the highest level of customer care are the principles of our business.

Email us at enquiries@shamrocktrains.com, or phone us on 07759 310098.