Few luxury trains evoke such passions as the Night Ferry – a train service that linked London and Paris and in time several other European destinations – making it Britain’s only truly international train. Night Ferry conjured many different images but encapsulated it was extremely comfortable, elegant and simply the most convenient and civilised way of travelling between Europe’s pre-eminent cities without the need to travel by day. The Night Ferry was the haunt of well-heeled businessmen, American tourists, in modern parlance ‘media celebrities’, aristocracy and royalty, civil servants, diplomats and, of course, the professional spy. The sleeper service was provided by Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits (CIWL) – also known as Wagon-Lits – who had operated similar services like the Orient Express across Europe for the best part of a half a century previously.

Certainly, the Night Ferry was an unique experience but well supported and even in the 1960s when air transport began to present a viable alternative, the service enjoyed patronage and occupancy rates many luxury hotels would have jumped at. The sleeper service attracted repeat guests and as David St John Thomas and Patrick Whitehouse in their book ‘A century and a half of the Southern Railway’ comment “…most passengers swore by the train, especially enjoying the comfort of lying out in privacy if the sea were rough. More usually it was a gentle motion of the waves that induced sleep”. In similar prose author Michael Williams in ‘The Trains Now Departed’ writes “But it was rare passenger who was not eventually soothed to sleep by the lullaby of the ship’s turbines”. There was something about the Night Ferry that was alluring and very special. Whilst the luxury element of the Night Ferry was clearly evident less consideration was given to foot or walking passengers not using the CIWL sleeping cars – the idea of introducing coach reclining seats on trains was not on the agenda until the late 1960s – crossing the channel at night may have been a less memorable event although they would have had the same access to quality dining facilities.

Before the Night Ferry’s first commercial journeys in October 1936 there had been several attempts over the years to establish an English Channel train ferry service. In 1872 a bill went before Parliament but was defeated; a subsequent proposal in 1911 was scuppered because of concerns on the horizon over events gradually taking place in Europe. WW1 and military supply demands did however, provide the technological capability and experience of regularly moving locomotives, carriages for ambulance trains, armoured wagons and low-loaders carrying tanks and freight/goods wagons carrying supplies to and from the Continent. Military train ferry services were developed from Southampton to Dieppe in December 1917, from Richborough, a few miles north of Dover to Calais and Dunkerque and in February 1918 from Newhaven to Dieppe all designed to support a final push on the war front.

Quite naturally, a cross-channel train service was closely entwined with continually delayed plans for a channel tunnel. Sir Edward Watkin, Chairman of the Great Central Railway had promoted a parliamentary bill to construct a tunnel in 1881 but never getting beyond pilot drilling. There had been other efforts in the intervening years but in 1929 a British Royal Commission was established to examine the feasibility of a channel tunnel. After wide-spread consultation the idea was eventually rejected by the Defence Committee in 1930. This provided Southern Railway with a chance to resurrect plans for a suitable train ferry service. Southern’s general manager Sir Herbert Walker had met Lord Dalziel, chairman of the management committee of CIWL in Calais on 9 December 1922 at the inauguration event of the glamorous Calais-Méditerranée Express, better known as Le Train Bleu – the Blue Train. Some 40 steel sided sleeping carriages for CIWL’s new luxury train and other services elsewhere in Europe had been built by the Leeds Forge Company so the seeds for Anglo-French commercial co-operation on a grand scale had been sown. But the idea of linking the crossing between England and France took many more years to firmly take root precipitated by a financial crisis that was to engulf the western world.

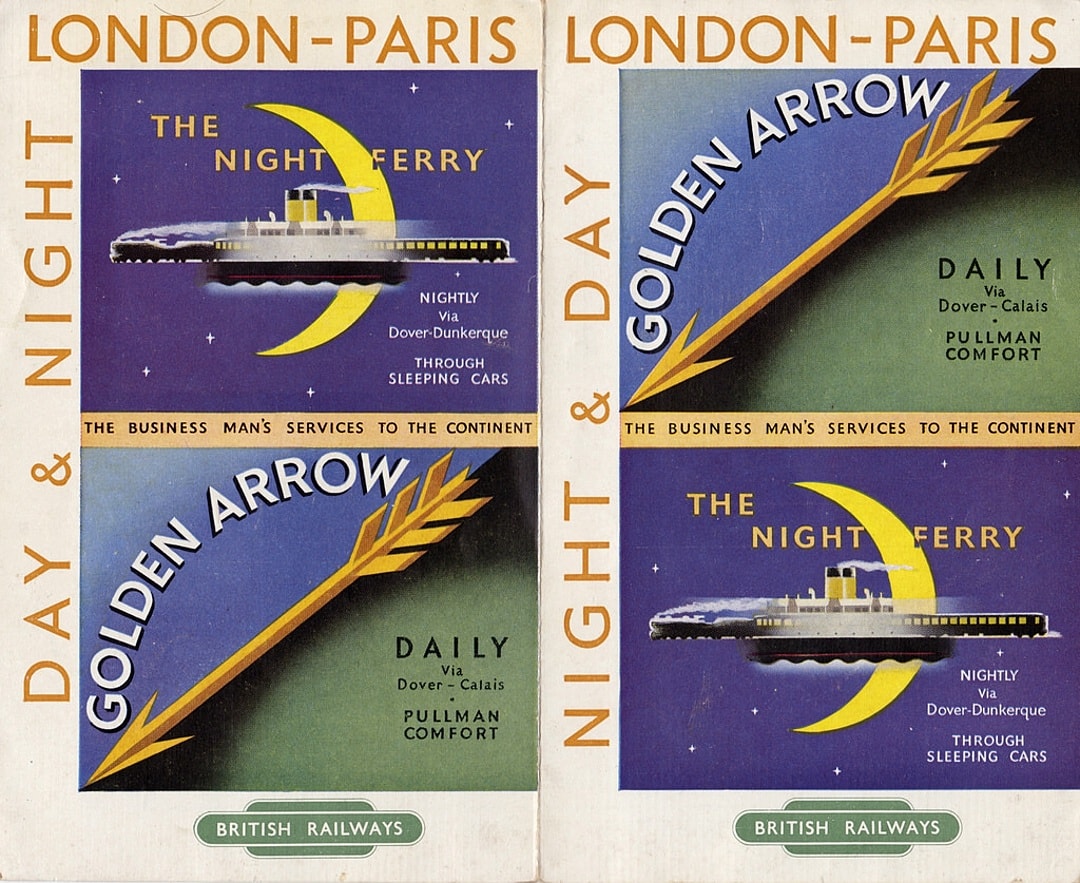

With railway grouping in 1923 the newly formed Southern concentrated its short sea boat train operations at London Victoria; the terminus provided up to seven weekday services linking Britain with France. The London-Paris Golden Arrow became the jewel in the crown of day-time services commencing operations on 15 May 1929. The launch coincided with the delivery of Southern’s new luxury steamship TSS Canterbury which had a capacity for some 1,700 passengers. In July 1930 the Golden Arrow was appointed with eight renovated Pullman cars: The French had been running their counterpart Calais to Paris express Pullman service (La Flèche d’Or) since September 1926 but Southern’s management held back until they could provide a distinctive and memorable offering. For the 250 to 300 de-luxe first-class travellers aboard the Golden Arrow the TSS Canterbury provided exceptionally spacious surroundings for the crossing. However, this was not to last as the economic downturn of the early 1930s downgraded the Golden Arrow from its exclusive first-class Pullman preserve with the train then having to accommodate a mix of first and second-class passengers together with Pullman first class passengers. Conditions on the Continent were no better forcing the French to make a similar dilution to their Pullman operation. Notwithstanding, the combined Golden Arrow/Flèche d’Or service became one of the world’s best known luxury trains: A comparable night-time service prompted serious consideration as the company continued to receive complaints from users of luxury boat trains that the services weren’t quite luxurious enough. In reality the idea was never far from the mind of Sir Herbert Walker as prospects for a channel tunnel were still distant dreams, expensive commercial flights were still in their infancy so the only effective way for travellers to reach the Continent was by train, boat and train.

With railway grouping in 1923 the newly formed Southern concentrated its short sea boat train operations at London Victoria; the terminus provided up to seven weekday services linking Britain with France. The London-Paris Golden Arrow became the jewel in the crown of day-time services commencing operations on 15 May 1929. The launch coincided with the delivery of Southern’s new luxury steamship TSS Canterbury which had a capacity for some 1,700 passengers. In July 1930 the Golden Arrow was appointed with eight renovated Pullman cars: The French had been running their counterpart Calais to Paris express Pullman service (La Flèche d’Or) since September 1926 but Southern’s management held back until they could provide a distinctive and memorable offering. For the 250 to 300 de-luxe first-class travellers aboard the Golden Arrow the TSS Canterbury provided exceptionally spacious surroundings for the crossing. However, this was not to last as the economic downturn of the early 1930s downgraded the Golden Arrow from its exclusive first-class Pullman preserve with the train then having to accommodate a mix of first and second-class passengers together with Pullman first class passengers. Conditions on the Continent were no better forcing the French to make a similar dilution to their Pullman operation. Notwithstanding, the combined Golden Arrow/Flèche d’Or service became one of the world’s best known luxury trains: A comparable night-time service prompted serious consideration as the company continued to receive complaints from users of luxury boat trains that the services weren’t quite luxurious enough. In reality the idea was never far from the mind of Sir Herbert Walker as prospects for a channel tunnel were still distant dreams, expensive commercial flights were still in their infancy so the only effective way for travellers to reach the Continent was by train, boat and train.

Following the British rejection of a channel tunnel Sir Herbert was keen to promote a through London-Paris train using a ferry. At a board meeting on 27 November 1930 he proposed such a service between Dover and Boulogne. The following month the Southern Railway board were informed of Nord’s investigation of a freight ferry across the channel. They were told in no uncertain terms that they must not let such potentially lucrative opportunities fall into competitor hands. The French were also considering an LNER sponsored alternative between Harwich and Calais (a Harwich and Zeebrugge freight train ferry had been successfully established in 1924) and proposals to develop the port at Tilbury from which a mail boat service had operated between Tilbury and Dunkerque from 1927 until April 1932.

Southern now made their first overtures to operate a night passenger service and consideration of a variety of routes and ports took place. In June 1931 the Southern announced that they would supply ferries and a terminal at Dover. A Dover-Boulogne route was considered as the best route option but the company prevaricated about a final decision until the French threatened to support a rival offer. The Southern Railway board finally sanctioned the introduction of train ferry for a night service between London and Paris on 19 October 1932 – this decision taken at the height of the slump but a strong business case and a commercial logic that better days would return underpinned board approval. A month later Dunkerque was announced as the preferred Continental location as it was an enclosed port unaffected by tidal rise and fall with French company Société Anonyme de Navigation Angleterre-Lorraine (ALA) agreeing to provide the terminal facilities. A formal announcement and application for tenders duly took place. ALA was in an ideal position to develop French operations as they had already acquired a number of ferries from LMS for the Tilbury-Dunkerque mail boat train. This service was later transferred to Folkestone on 1 May 1932 so relationships with Southern management were well established. In addition, ALA had also developed onward train connections to Paris-Nord.

On the English side Dover Harbour was selected as the terminal since Southern had already concentrated most of their boat train/ferry operations there. The port was well-developed for cross channel purposes enjoying comparatively close access to London which could be reached within two hours. But the choice of Dover did not come without complications. There were enormous engineering problems to overcome because of the harbour’s twenty-five foot tidal rise and fall, rough Channel seas compounded the construction process which also suffered from leaking from fissures in the porous chalk beneath the dock floor. These difficulties were eventually overcome and a train ferry berth was built within Dover Harbour. Work began in 1933 requiring the construction of an enclosed dock more than 400’ long and 70’ wide sealed with a pair of gates together with a long-length loading ramp or linkspan to meet the specially designed train ferries. Once the ferries were inside the sealed dock the level of the water was then either raised or lowered depending on the state of the tide – the pump house capable of moving nearly 750,000 gallons of sea water per hour. ‘Dover Ferry’ was probably the only timetabled passenger station on the British railway network without platforms.

In 1933 a special model of twelve CIWL Type F (for Ferry) British loading gauge sleeping cars were designed. They were built between November 1935 and May 1936 by Ateliers de Construction du Nord de la France Blanc-Misseron carrying no: 3788 to 3799. Between 1937 and 1947 a further six Type F sleepers were built no: 3800 to 3805 but completion was delayed until hostilities had ended. Following CIWL instructions delivery took place before the war commenced but they were incomplete as their bogies were removed to prevent the Germans using them. In 1952 a further seven Type F sleepers no: 3983 to 3989 were constructed to replace the five original coaches that were lost to the war. All of the original sleeper cars had been requisitioned by Mitropa. Nos: 3788 and 3795 simply disappeared in the six year conflict whilst 3793, 3796 and 3799 were rebuilt as Mitropa dining cars and never returned.

A feature of the F Class vehicles was that there were doors at one end of the coach only. The reason for this being they were shorter and the vestibule space at the non-door end was converted for use by the attendant and for storage of equipment. The gangway to the next coach was retained for access to dining cars. Another F Class feature was the sides above the waistline were tapered in a few degrees in order to clear obstructions such as tunnel walls. The carriages had nine two-berth cabins (some adjoining each other) which meant the total number passengers per carriage could vary between nine and 18 – effectively a very selective club as even in the busiest of times the ferries rarely transported more than ten sleeping carriages.

To the casual observer at London Victoria Night Ferry was certainly an unusual looking train. The CIWL sleeping cars and the accompanying four-wheeled baggage vans were painted metallic blue like those of the iconic Le Train Bleu – the colours evoking a mixture of gooseberry, blackcurrant and rhubarb pastels. In addition, pre-war there were umber and chocolate brown liveried 12 wheeled Pullman coaches providing a full catering service, standard Olive green painted SR Maunsell coaching stock together with the motive power – invariable locomotives were out of sight when the train was long.

The Southern experimented with various locomotives such as their 4-6-0 Lord Nelson and King Arthur classes (normally used to haul Continental and ocean liner boat trains) but they were unable to handle the excessive weight of Night Ferry single-handed. The solution was a double-headed pairing of not so modern 4-4-0 D1 and/or L1 locomotives. Post-war the motive power altered with the introduction of the nautically themed and more powerful 4-6-2 Merchant Navy Pacific class locomotives (each one named after shipping lines) which could accommodate the normal make-up of the Night Ferry. The Merchant Navies in their resplendent new Malachite green liveries were soon to become regulars. During this period the complement could have been restricted to only three or four sleeper coaches for each journey as a number of carriages were destroyed during WW2 – the rest of the train being made up of a rake of extra Maunsell and new Bulleid coaching stock. However, in the first six months of 1952 seven new F class CIWL sleepers were introduced to combat war-time losses making a total fleet of 20 sleepers to meet increasing demand for the service.

As well as Merchant Navy classes Night Ferry would also be hauled by the similar but lighter 4-6-2 West Country and Battle of Britain classes but these would require piloting with another 4-4-0 D1 or L1 when pulling heavier loads. In the early 1950s the Night Ferry could also be seen hauled by the new generation 4-6-2 Britannias such as no: 70004 William Shakespeare and no: 70014 Iron Duke who would also work the prestigious Golden Arrow. These new locomotives appeared in the new British Rail Brunswick green liveries which remained unaltered until electrification took over on both sides of the channel as the motive power in 1959. Due to the extensive electrification work taking place in south east England weekend haulage for Night Ferry remained steam traction (Merchant Navy 4-6-2s with 6000 gallon tenders) for several years.

Whilst the CIWL sleeper coaches came over with the ferry, foot passengers had to board awaiting coaches which altered on a frequent basis according to season and the total number of combined sleeper and foot passengers. Typically post-war the SR coaches attached at Dover Ferry terminal could comprise a restaurant and kitchen car, buffet car, corridor first, two corridor seconds, another restaurant and kitchen car, and a first-class brake and over a ten year period they would go through three sets of livery changes from Malachite green, to BR blood and custard and latterly BR green. The train breakfast was an essential part of the travelling experience and although post-war the British portion of the Night Ferry did not carry Pullman cars the catering services were still provided on SR stock by the Pullman Company.

On the French side Ferry Boat de Nuit was headed in both Nord and SNCF days by 4-6-2 (2-3-1E) Chapelon Pacific locomotives until electrification of the line. These powerful steam locomotives also handled the Paris-Calais section of the Flèche d’Or. A range of larger continental coaches accompanied Ferry Boat de Nuit together with a CIWL dining car situated between the sleeping cars and the seating coaches. In the early years of Ferry Boat de Nuit this would have included a luxury dining car built in 1926 originally forming part of the French president’s train but in 1952 this was replaced by a larger CIWL WR 56 seater restaurant dining car.

In the Nord period seating coaches would comprise two first-class and five second-class coaches both in green livery with oval windows. In the first SNCF epoch this was changed to two Rapide Nord first-class and four Rapide Nord second-class stock. In the 1960s these were replaced by six SNCF DEV INOX coaches and in the 1970s Ferry Boat de Nuit was up dated with up to six SNCF IIC Type stock. Although the Night Ferry F Class sleepers were smaller than standard Continental carriages they were not prohibited from working elsewhere in Europe. Two were included in the Nord Express and allocated at Gare du Nord as part of stock used on the Paris-Hanover train. Type Fs could effectively appear anywhere on the European network as indeed British Pullmans did in the past as special or supplementary vehicles.

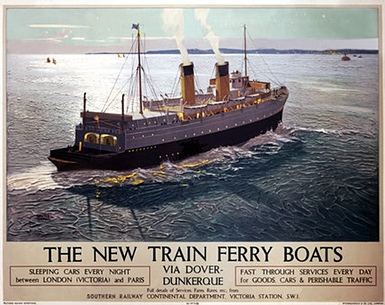

The last part of the Night Ferry equation was the three dedicated vessels built specifically for the service. The ships were designed to carry a maximum of twelve British loading gauge sleeping cars and associated baggage vans. The train deck on the ferries had four tracks which converged to two at the stern accessed via the loading ramp or linkspan. The vessels were built by Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson of Wallsend-on-Tyne. In July 1934 Twickenham Ferry was delivered followed by Hampton Ferry in November and in March 1935 Shepperton Ferry became the third ship for the unique service. The ferries were owned by Southern but as the new service would displace an existing French Folkestone Harbour to Dunkerque run operated by ALA, the French authorities demanded that one of the ferries be placed under the French flag. Twickenham Ferry was transferred to ALA on 22 September 1936 and manned thereafter by French nationals. Initially, the three ferries were coal-fired but post-war they were converted to oil burning.

The last part of the Night Ferry equation was the three dedicated vessels built specifically for the service. The ships were designed to carry a maximum of twelve British loading gauge sleeping cars and associated baggage vans. The train deck on the ferries had four tracks which converged to two at the stern accessed via the loading ramp or linkspan. The vessels were built by Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson of Wallsend-on-Tyne. In July 1934 Twickenham Ferry was delivered followed by Hampton Ferry in November and in March 1935 Shepperton Ferry became the third ship for the unique service. The ferries were owned by Southern but as the new service would displace an existing French Folkestone Harbour to Dunkerque run operated by ALA, the French authorities demanded that one of the ferries be placed under the French flag. Twickenham Ferry was transferred to ALA on 22 September 1936 and manned thereafter by French nationals. Initially, the three ferries were coal-fired but post-war they were converted to oil burning.

They could carry some 500 passengers for the overnight sea voyage. When the ferry was heavily booked a second relief boat train for foot passengers would run ahead of the Night Ferry from Victoria. For those not travelling in CIWL sleeping cars some sleeping accommodation was provided in separate ladies and gentlemen saloons as well as separate first and second-class designated restaurants. Post-war the ferries became single-class vessels. On 28 July 1951 a new diesel-powered train ferry was added to the roster by SNCF. The Danish built Saint-Germain was of the latest design and would last operationally for a further 37 years. Both Shepperton Ferry and Hampton Ferry provided relief capacity service out of Stanraer following the Princess Victoria disaster in the northern Irish Sea on 31 January 1953; Hampton Ferry continued support every summer until 1961.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the three original Night Ferry vessels was their additional capability to carry 25 private cars in a garage facility on the upper deck of the ship. Access was side-loading via a concrete ramp alongside the vessel which began in June 1937. Post WW2 this was extended to up to 100 cars and their passengers providing a significant contribution to what was to become BR’s drive-on car ferry business. When not on Night Ferry duty the ferries provided a valuable additional resource for moving vast quantities of perishable foodstuffs from the Continent and in return outward cargoes consisted of British manufactured cars, tractors and machinery destined for European export markets. The ships could each accommodate up to 40 special loaded goods wagons as well as motorised heavy goods vehicles. The scale of importing European produce was so significant that by 1960 a large new depot was built by BR at Hither Green in south London for onward distribution of foodstuffs that had been hauled by rail via the Dover train ferries.

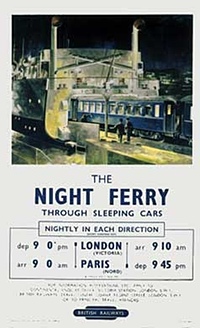

The respective journeys would begin at either London Victoria or Paris Gare du Nord; for many travelling on the Night Ferry was simply a thrill. At Victoria passengers wishing to travel incognito could simply leave the Grosvenor Hotel via a back entrance door that opened on to the station concourse but everyone had to negotiate passport control and customs. Once through the tiny passport control room sleeping and foot passengers were separated. Sleeping passengers on platform 2 were directed towards one of the glamorous blue and gold sleeping car berths – T.S. Elliot referred to the cosy compartments as “little dens”. Foot passengers would stroll down platform 1 to the point where they were beyond the sleeping cars to the awaiting restaurant and buffet cars and ordinary boat train coaches.

The respective journeys would begin at either London Victoria or Paris Gare du Nord; for many travelling on the Night Ferry was simply a thrill. At Victoria passengers wishing to travel incognito could simply leave the Grosvenor Hotel via a back entrance door that opened on to the station concourse but everyone had to negotiate passport control and customs. Once through the tiny passport control room sleeping and foot passengers were separated. Sleeping passengers on platform 2 were directed towards one of the glamorous blue and gold sleeping car berths – T.S. Elliot referred to the cosy compartments as “little dens”. Foot passengers would stroll down platform 1 to the point where they were beyond the sleeping cars to the awaiting restaurant and buffet cars and ordinary boat train coaches.

Sleeping passengers were met by brown uniformed CIWL conductors and shown to their berths. From the moment the guest stepped on to the train a very special atmosphere was guaranteed. The compartment interior walls were of 1930s design with metal painted brown to look like wood, and steel blue. The only real differences in the sleeper compartments were the luggage racks which contained life jackets and netting to stop luggage falling when sea conditions were rough. The made-up bunk beds (which could be converted into brown velvet sofas for day-time travel) had crisp white cotton sheets and traditional monogrammed brown wool blankets which were later to be replaced by blue blankets of Scottish woven tartan.

If a customer did not want to adjourn to the dining car drinks and snacks may be brought to the cosy sleeping compartment which also contained a few extra luxuries as mementoes of the trip. Given the train was a late departure many passengers choose not to eat in the dining car having eaten earlier in the evening but they might have been missing out on a gourmet treat since post-war rationing did not apply to these respective national showcases. The dining car came into its own the following morning for ‘le petit déjeuner’ – CIWL describing it as Le Meat Breakfast – a dining car ritual on the French side that stayed unchanged for seventy 70 years. The 1950s and early 1960s were the hay-day of the Night Ferry; the service which was increasingly popular never lost its aura of exclusivity and continued to attract many VIPs as in June 1956 the train became first-class only. The following summer Night Ferry added a new destination with the introduction of a through sleeping car service to Brussels normally made up of one or two cars. The Brussels sleeping cars together with first and second-class foot passenger coaches had to leave Dunkerque before the first-class only sleeper service to Paris. Electrification and fast locomotives guaranteed a rapid transit from the port to the capital – ideal for important early morning meetings.

At the end of 1967 a new winter sports venture to Strasbourg and Basle commenced but this only lasted two seasons due to increased competition from more dependable air services. During the 1970s Night Ferry saw a continued downward spiral in passenger demand as the service became a little ‘frayed around the edges’. Although work on the proposed channel tunnel stopped in 1975 it was still downhill for the service as the CIWL staffing contract ended in 1976 being replaced by BR and SNCF staff. As the train was purported to be losing £120,000 a year both organisations claimed they could not warrant the outlay for long overdue replacement stock. The life-expired sleeping cars had had their day. On Friday 31 October 1980 – the same day as the closure of the London Evening News – with seated passengers already carted off to a separate EMU – the end came of perhaps of the most celebrated luxury railway service Europe had seen. There was a considerable degree of excitement at Victoria particularly with droves of the media in attendance. At 21.25 headed by a somewhat sombre-looking mixed-traffic diesel-electric locomotive no: 33043, Night Ferry made up of just seven sleeping cars, two luggage vans (the first fourgon having ‘Goodbye’ written on it) and one ordinary Mk1 BSO coach made its final outward journey from Victoria. A replica style headboard made by staff from Stewarts Lane was placed on the front of the locomotive but it didn’t return on no: 73142 Broadlands which brought in the inward leg to Victoria the following morning. As Derek Winkworth in his book ‘Southern Titled Trains’ comments “BR had finished with their sole international through train and could devote its energy to the commuter traffic – it was all over!” But the memory of Britain’s truly first international train still stays alive.

For further information see the Great Cross-Channel Boat Train Expresses chapter in Boat Trains: The English Channel & Ocean Liner Specials by Martyn Pring.

Shamrock Trains is a provider of 0 Gauge ready-to-run model railways and similar associated products. We provide a high quality, professional and personalised service to our customers. We are a highly knowledgeable operation providing specialist advice to customers around the world; we believe we are one of the few model railway retailers to operate in this way. Honesty, integrity, providing value for money and the highest level of customer care are the principles of our business.

Email us at enquiries@shamrocktrains.com, or phone us on 07759 310098.